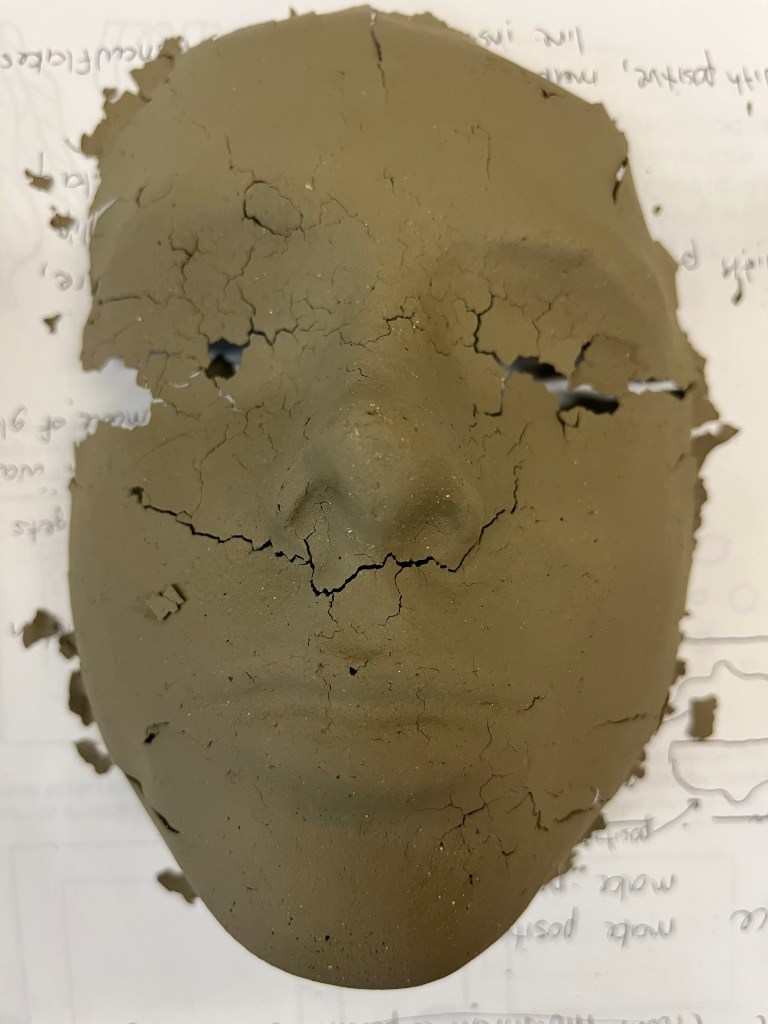

In my previous post, I told the story of the work I’ve been doing lately and mentioned that I had more to say about the clay slip mold of my son’s face and what it conveys.

Really, I have a lot of thinking to do about the direction my work is going and my use of this material to create ephemeral forms in general. This semester, I’m taking a directed reading course with Lindsey French, so this is the perfect opportunity for me to try to understand what my work means to me and what I wish to say with it. This is critically important as I approach the time in my MFA program for developing my graduating exhibition, the equivalent of a thesis.

Browsing the aisles of the Archer library recently, I lucked out by pulling from the shelf (Im)permanence: Cultures in/out of Time. This is a book covering the proceedings of a conference of this title that took place to mark the one hundredth anniversary of Albert Einstein’s publication of his article on relativity. The conference, and this book, “examine the state of time as represented in the arts and in culture at the beginning of a new century” (5). In its intro, the editors state that,

[t]he late twentieth century has been called an era of ephemerality. One hundred years after Einstein, time became a fungible commodity, a matter of interpretation rather than of measurement. Artists all over the world seized on the idea of the impermanent, building transience into the form and content of their art. (6)

The chapter of this book that most interests me (and more than anything I’ve read in a long time), is Mary O’Neill’s “Ephemeral Art: Mourning and Loss.” As a way of getting started with this term’s reading and thinking, I’m going to connect several ideas from this chapter to my own thought and work processes.

O’Neill starts with a definition of ephemeral art as not simply temporary works, but “works in which the decay or disappearance of the work over the course of time is an intrinsic element of the piece. In these cases the decay and/or disappearance is intentional and is an essential aspect of what the work communicates” (88).

This connection O’Neill makes between ephemerality and mourning in this chapter is precisely how I’ve been thinking about my practice—the ephemeral nature of all of my works has been purposeful, melding content and form.

I was thrilled to see someone connect this type of work with the grieving process in the way O’Neill has done: “[E]phemerality is a means of communicating mourning and of bearing witness to the obsessive remembering associated with what Freud calls ‘grief work'” (88). For me, my work is about loss. It makes sense that on top of this work’s contextual layer of which I am consciously aware are other connections between this work and my grief. I hadn’t considered, for instance, that using this local material, even studying it closely, is likely an act of “obsessive remembering.” O’Neill later elaborates on the process of mourning:

“Mourning is the reaction to the loss of a loved one or an ideal, a belief, for example in truth or the immortality of one’s home or country. It refers to the painful process of relinquishing emotional ties to the lost person or object through a process of reality testing. This process involves periods of obsessive remembering, as the mourner seeks to conjure up the lost person and to replace him or her with an imaginary presence. This magical resurrection allows the mourner to prolong the existence of the lost person, which is the main object of Trauerarbeit (grief work). This is a very difficult and painful process made even more difficult by the fact that when we mourn the loss of another we are also mourning the loss of part of the self.” (92)

I appreciate that O’Neill recognizes that one can mourn an ideal or a belief, such as a belief in the immortality of one’s home. However, nowhere else in this chapter does O’Neill really stray into the area of environmental loss. Her focus throughout is on the loss of people or objects. In my practice, I’d like to expand on her work with this topic to consider the mourning needed as a result of environmental destruction. What, I wonder, does she have to say today about climate change and the in-our-face impermanence of everything alive right now (perhaps excluding fungi and waterbears)? I’d like to know what she and Glenn Albrecht, the Australian philosopher who coined the term solastalgia, would chat about.

My jaw dropped when I read of Freud’s poet friend in this chapter:

“In his 1915 essay On Transience Freud describes a conversation he had with a poet friend while out walking. The young poet was unable to enjoy the beauty of the scene surrounding him because of his awareness of the inevitable decay of all natural splendor, in fact the transience of everything, both natural and human creations. Freud states that this despondency is one of two possible reactions to the knowledge of the inevitability of death and decay, the other being a rebellion against the facts—an assertion of, or a demand for, immortality” (90).

I definitely suffer from the former response to my “knowledge of the inevitability of death and decay;” that is, my experience over the past year, since our summer of near-constant smoke and heat domes, mirrors that of Freud’s friend. A major setback in my recovery has been that nature, normally that great balm for emotional distress, is the very source of my grief, so spending time in it only triggers more pain. However, I’m not sure where my despondency really stems from exactly. Unlike for Freud’s friend, I don’t think that its cause is my own mortality, and neither am I bothered by the death of any particular individual tree or bird that I see. I fully recognize the necessity for death in nature, which includes my own. What saddens me is the loss we are seeing during this sixth mass-extinction event which we have caused. It’s the injustice and the huge loss, larger and faster than previous extinctions, that stops me in my tracks.

I’m not sure, in other words, where the usefulness of Freud ends in this conversation, as the world is now in an entirely different situation from the one in which he lived. O’Neill writes that “Freud’s description of the ‘old myth of redemption’ is particularly significant for our understanding of the need for permanence in relation to artworks. The myth of the immortality of art represents a victory of humankind over nature” (91). Okay, but what if one is quite certain that humankind, as a result of destroying nature, is in fact destroying itself? This notion of the “immortality of art” can’t apply in a world where there are no people left to view it. Or can it?

O’Neill writes that permanence is a requirement of the art world for both the institutions (adding to and preserving their collections) and to the art-makers (establishing themselves and ensuing their perpetual existence); however, “underlying this is a greater emotional need for our cultural objects to survive intact—we need to know that some things will always be safe, will always be ‘sacred,’ and that through them some part of ourselves will survive” (89). I’d say that we now know that nothing will be sacred or safe as the future is unsafe, and here is where ephemeral work makes sense for me. It’s not so much that “ephemeral art engages with our fear of mortality both in ourselves and in others” (89), but more that it embodies our fear of global catastrophe at an apocalyptic scale, or, if it’s not about fear for others, it is at least an acknowledgement of our collective precarity and transience.

O’Neill does speak about mourning in situations of “disenfranchised or ambiguous grief” (95). Taking from Kathleen Gilbert, she shares that there are “deaths that society does not prepare us for or provide guidelines for the appropriate mourning behavior” (95), and that:

“This lack of social recognition can increase the sense of loss, and according to Gilbert, ‘expresses itself in a variety of physical, psychological, or behavioral manifestations.’ One of these behavioral manifestations for artists who have experienced loss, especially disenfranchised loss, is an engagement with transience. At a time when the only constant in their life is transience, they seek meaning not by trying to create something permanent, but by embracing the transient and embodying it in their work.” (95-6)

Yes. This makes a lot of sense. I’m going to delve further into this topic (ephemeral art as a response to loss) in coming weeks, also looking at the value of art in general, historically and in the present. I hope that this research will give me a sense of where to take my work from here.

O’Neill, Mary. “Ephemeral Art: Mourning and Loss.” (Im)Permanence: Cultures In/Out of Time. Penn State UP, 2008.

O’Neill subsequently published her doctoral thesis on this topic.

As always, Amy, I am enjoying the process that you, as an artist, are going through. I would like to point you also in the direction of impermanence as in Asian belief systems where change birth, life, decay, and death are celebrated and not feared but embraced. Best of luck to you.

LikeLike

Thank you, Mary Ann. I’m always happy to hear from you. Yes, I’ve considered Buddhist teachings in the past; if only I could learn to live by them! 🙂 Stay well.

LikeLike