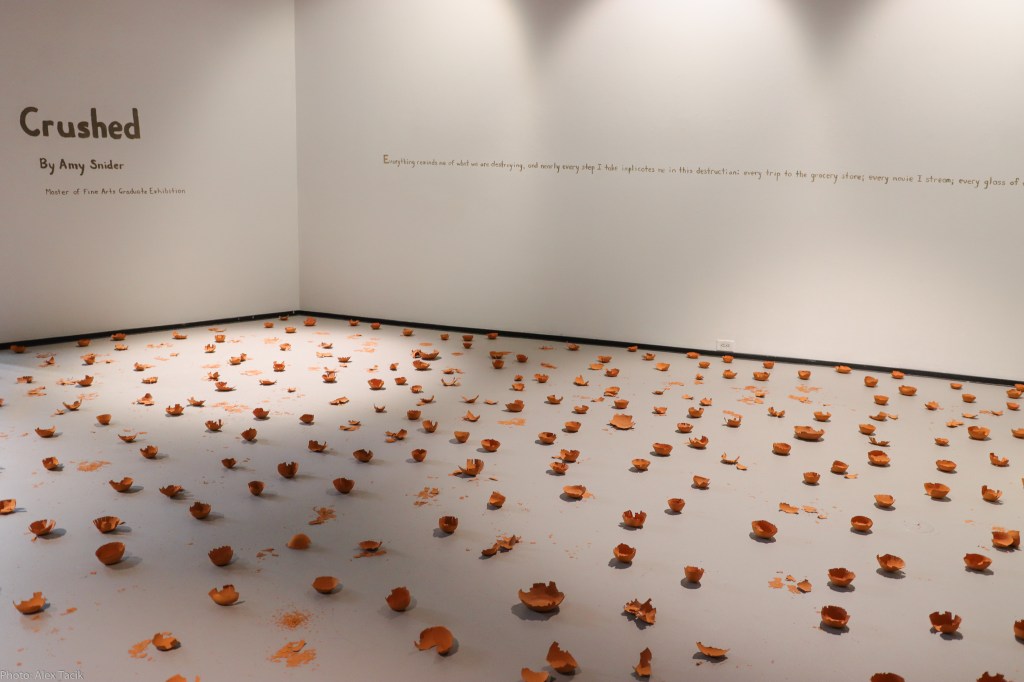

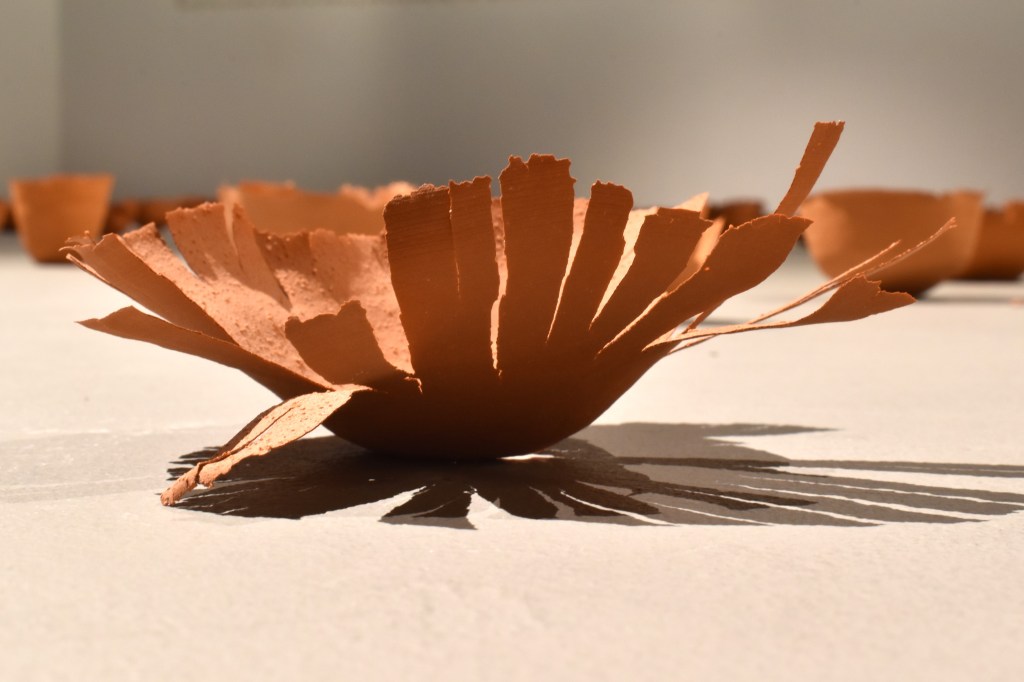

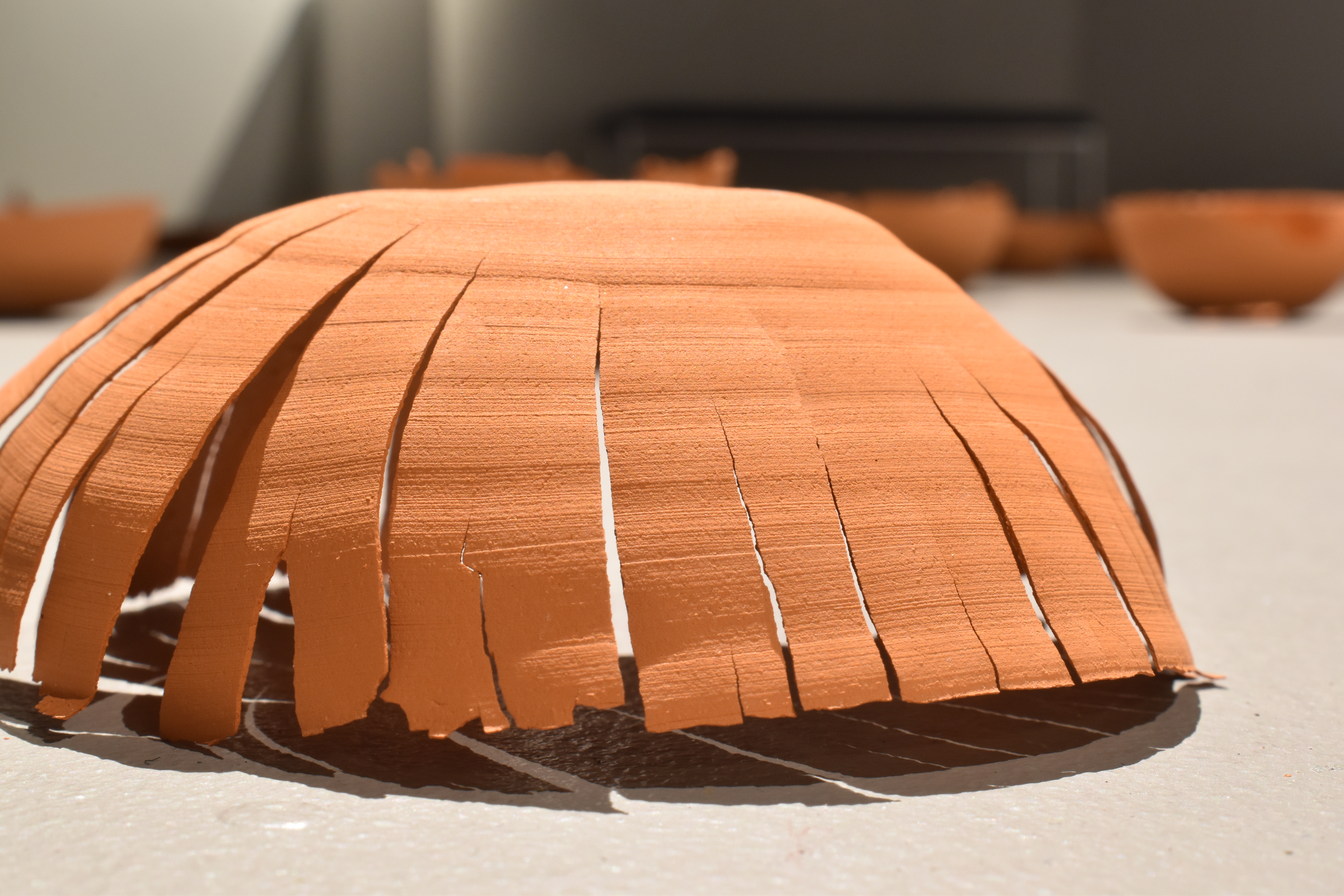

This past September, I made a trip to visit Miriam Körner at her home near LaRonge, Saskatchewan. I’d first met Miriam on an early-Covid Zoom event for environmental activism. She was supposed to present on the non-profit organization she’d created to raise awareness of the need to protect peat bogs, For Peat’s Sake, but sadly we ran out of time for her presentation. For some reason, one of us then friended the other on Facebook after that meeting, and we followed each other’s posts for another four years until we met in person last summer at a mutual friend’s, Kiké Dueck’s house for dinner. Kiké is the amazing 12 year-old friend I met in the gallery during my MFA exhibition, Crushed. I love that I’ve met so many great people simply by getting involved in things that are meaningful to me. (And I suppose I also have Mark Zuckerberg to thank, blah).

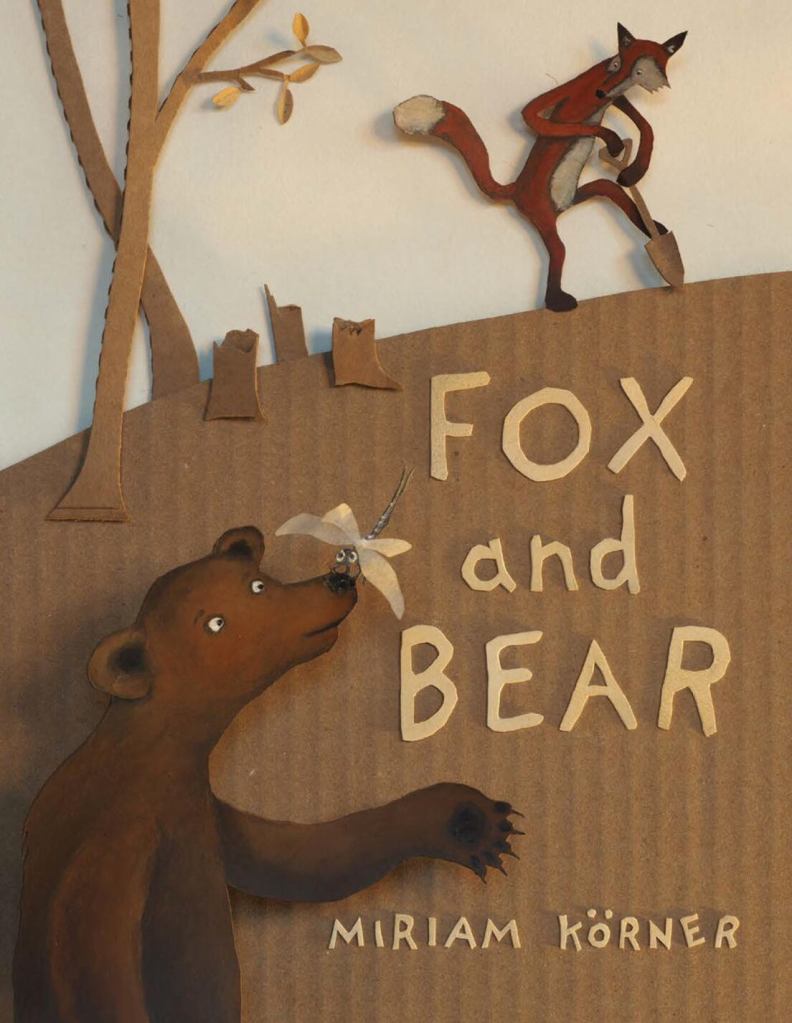

Miriam is an award winning artist and writer. She brought Kiké and their siblings a copy of the children’s book Fox and Bear she’d written and beautifully illustrated with photos of dioramas she created from discarded cardboard and paper.

I love that this forest fable is sourced from recycled paper, former-trees; like my work about land which I make with clay I dig up, Miriam’s book speaks about the forest through the forest. It is coalescence of form and content, meticulously crafted with everything necessary to tell this story, and not a word nor wood fibre more. If I learned anything from my time in my MFA, it was to strive for this in my work. I knew immediately upon reading this book that I had to spend some time with Miriam and the land she loves.

Below are my journal entries from the two full days I spent with Miriam (with photos and extra notes added in italics):

September 6th, 2025

What a wonderous day. It started, after a quick breakfast, with a stop at a burned forest on our way to Missinippi to pick up a canoe. This was unlike any place I’d ever seen. In places, it was a complete burn, down to sand and solid rock of the Canadian Shield.

Everything else there appears gone*—the trees and other plants, leaf litter, mosses, lichen, fungi—everything, even the soil. Only tiny conical stumps, black and pointy, remain of entire trees. It looked somewhat like an archeological dig-site in places.

I’d been anxious about this trip. When the fires that burned these forests were raging last summer, the smoke comprising their particles blanketed me in fear and grief—grief for the life that had vanished into air (is that burnt warbler I smell?), and fear for what the future holds with this pace of global heating. The drive up reinforced these feelings: kilometers of burn on both sides of the highway, and then this, a car abandoned on the side of the road during the evacuations—

*However, what was unescapable in this place today were the spurts of bright colour popping out everywhere. Green grasses and other plants are already abundant: the showy purple of fireweed and tiny patches of orange mushrooms jump out of the black blanket beneath, resilience-trophies.

Even the charcoal remains were beautiful with their metallic sheen and wabi sabi shapes. I would have been surprised by this, even a bit mortified, but Miriam had told me on the phone that while keeping a fire off her cabin a few years ago, she also appreciated its aesthetic qualities in several ways. Perhaps it’s beautiful because life is beautiful, and fire is not only a destroyer, but also a provided.

The frequency and intensity of forest fires now is still alarming. Some places we walked through had been burned ten years ago as well, and there we found fewer tree trunk remains and less new growth. This soil, with its recovering rhizosphere and mycorrhizae, was hit extra hard.

Moonscapes, people call these areas of total burn, Miriam told me.

At one point, we found six burnt tree trunks all pointing towards a centre spot as if someone had let go of a handful of Pick-up Sticks. I was sure we’d come across a piece of land art: someone had been there to make this aesthetic choice, right? I asked Miriam if she thought the design was manmade, and she said, “yes, of course—it’s the Anthropocene!” It took me a moment to get the joke. Sure enough, we came across other examples of this “art.”

Then, walking on, we were suddenly in an oasis: we’d hit a patch of muskeg, also known as peat bog. Sphagnum moss over two-feet high—moss upon moss upon moss, none of it attached to anything but merely feeding off the air and water—cushioned our steps so much it was difficult to stay upright.

I fell softly to my knees and gently pushed my hand into this material. Down went my arm, my fingers searching for an end, until I was nearly at my armpit when I hit water, then rock: an underground reservoir sat atop the impermeable Canadian Shield. In that cold water lay peat.

This is what peat is: the very bottom layer of these sometimes six-foot-tall ancient moss forests.

I pulled up a small handful of it to see it with my eyes, then squeezed to watch the water run out of it, like you do with a dish sponge before placing it beside the sink. Miriam taught me about the muskeg, how Indigenous people make bog tea, also known as Labrador tea, from it, and how they would store their food down in the peat, a type of natural refrigeration.

Bog plants are also rich with nutritional value. Tiny red bog berries dot the bright greens of the moss. Each bog berry plant is a single Christmas-light strand of around two inches, boasting one single, sweet berry. Mushrooms and plants of all shapes, sizes, and colours dot the green as well, some so small you have to be staring right at one to notice it’s there, and then you realize they’re everywhere, just like stars in the sky.

Muskeg are some of the oldest ecosystems on the planet, taking thousands of years to grow.

Yet we mine peat by clear-cutting the muskeg, giant machines bulldozing, slicing off this deep layer of life for the superabsorbent decayed material below it that is in every bag of potting soil you find in every garden centre. It’s also used as animal bedding. It says an awful lot about our species that we’ll dismantle an entire local ecosystem to plant our orchids and catch our cattle’s feces. I now better understand the urgency of Miriam‘s fight.

We stumbled on, above this ground-level aquarium. I lay down at one point and sank a few inches into the most perfect mattress—a natural memory foam, with zero off gassing. I like to imagine that I left one of my selves there, sleeping on that muskeg.

We then left to canoe Otter Lake in search of more muskeg. In a couple of weeks, Miriam has a weekend paddling trip planned for a group of 26 women, and she wants them to experience the peatland.

I’ve never canoed with anyone like Miriam. She and her husband, Quincy, have done trips up to 73 days and over 1,000km! Their canoe was handmade by a friend and is built for racing. It and her fiberglass paddles are extraordinary tools. I’ve never moved on water like this before. At one point, an otter family popped up from the glassy lake just in front of us, on its way somewhere. We watched each other for a while before they undulated away, their bodies long and Loch-Nessy.

We spent the rest of the day paddling and trudging through wetlands and forests, with a picnic stop on a rock in the middle of a shallow creek. Water, in all the shapes and bodies it takes, kept the moonscapes at a good distance–still there, but not everywhere.

It wasn’t until about 7pm when we quit the search and started the drive back to Miriam and Quincy’s cabin. Still, we couldn’t resist stopping briefly at MacKay lake to jump off a dock and swim with the sunset. The water was dark and clear. This was one of the best swims of my life, and probably one of my most extraordinary days.

September 7th

Another wonderous day, another burned forest, this one at Don Allen Trails in a provincial park where the fire renovations have helped with their “express checkout” process.

I collected ash and skeletons of dead trees to take home to Regina for artistic research purposes. Miriam showed me areas where the fire could have burned on forever; it was underground, a ladder fire—anytime it came to a tree with low, dry branches near the ground, it would set the tree aflame. Trees without low branches could be left untouched.

We walked through more patches of moonscape. In a few places, we couldn’t tell what ash and what was sand, everything blended in soft browns, greys, and ochres. Brushing it with my hand, I could see layers—white, black, orange—and feel the difference in touch. What had this place looked and felt like before the fire? What smells and sounds had been here, too?

The fineness of the ash reminded me of the Rocky Mountain glacial rock flour I love. Here, the process of erosion is taking place visibly. Rocks, even large boulders, had gotten so hot in the fire that they exploded and now lay in fragments. One piece I picked up had some kind of larva living on its underside, in the ash. Ants were here, too.

We drove to Bielby Lake, parking on a highway pull-out made for service vehicles. Miriam took the canoe on her shoulders and went forging ahead towards the water on an overgrown once-trail. She’s stubborn, like me. We paddled around the whole lake, picnicking this time on a tiny island where I couldn’t resist another swim. We got to the end of the lake where there was a wetland with forest in the distance. Miriam said she saw a portage trail and took off on it, but I didn’t see anything resembling a trail at all. Walking was some form of ungraceful tai chi, our legs raising high and landing each step cautiously, our arms swinging with the twist of our torsos. Under the cover of green lay rocks and fallen branches, with water below them. One foot would land on something solid, the next would go straight down. I fell several times and had trouble getting up. We went on and on as it started getting dark and Miriam gained distance far ahead, certain we were on a trail.

As we reached the forest line, though, there it was: a clear path in the trees. How did she know it was there? It had been invisible from the lake. Suddenly we were hiking on solid ground amid trees, plants, and a rainbow of mushrooms.

Then everything changed again: we’d reached muskeg, the muskeg Miriam had been hoping for. She taught me how to identify the three families of moss: feather, sphagnum, and club, each having hundreds of varieties. And pitcher plants! I couldn’t believe there were carnivorous plants in Saskatchewan. I have an African one hanging above my kitchen sink, and I’ve always felt that it was so exotic. Now I know that Northern Saskatchewan is exotic too.

We paddled back, me in the front spot again, with Miriam’s weightless paddle. I zoned out to the rhythmic sound of water dripping off the paddle as it sliced the air between strokes and we glided through the clouds. I could do this for days.

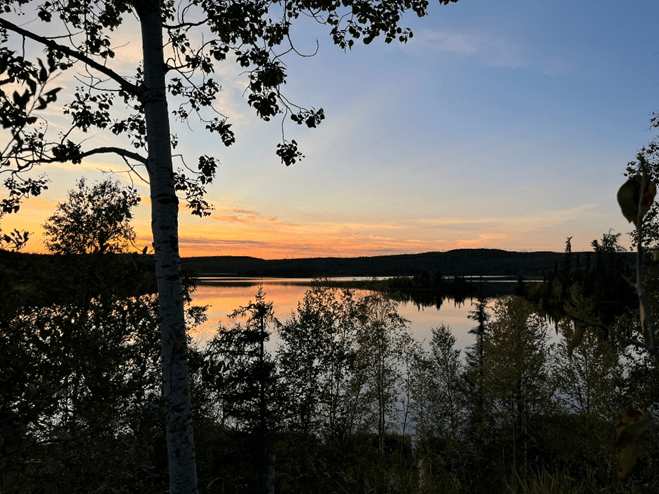

Then there was the lengthy drive home in the dark. We stopped to look at a beautiful burnt forest across a stretch of water. In front of us, we had it all.

At our feet were large beaver-felled trees. I think my cognitive abilities were maxed out from the two days of over-stimulation. I asked Miriam how beavers drag large tree trunks to the water. She said they don’t, they only take their branches. I asked why they fell the whole tree then. “Because beavers can’t climb trees.” We both had a very good laugh.😊

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thank you, Miriam, for everything you taught me on this trip, and for everything you do.