*Works in bold are ones I read from this term, Fall 2020; others are ones I’ve read in the past or plan to read in the future.

On Art (theory and criticism) & Art and Politics

Art in the Anthropocene: Encounters Among Aesthetics, Politics, Environments and Epistemologies. Edited by Heather Davis and Etienne Turpin. Open Humanities Press, 2015.

Art of the Encounter: Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics. Claire Bishop Source: Circa, Winter, 2005, No. 114 (Winter, 2005), pp. 32-35 Published by: Circa Art Magazine

Bishop, Claire. Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. London: Verso, 2012.

Bourriaud, Nicolas. Relational Aesthetics. 1998. Trans. Simon Pleasance and Fronza Woods. Dijon: Les presses du reel, 2002.

Chambers, Ruth, Amy Gogarty & Mireille Perron, eds. Utopic Impulses: Contemporary Ceramics Practice. Vancouver: Ronsdale Press, 2008.

Dormer, Peter, ed. The Culture of Craft: Status and Future. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997.

Jelinek, Alana. This is Not Art: Activism and Other ‘Non-Art’. London: I. B. Tauris & Co Ltd, 2013.

Bishop, Claire. Introduction to Participation. Edited by Claire Bishop. Edited by Claire Bishop. London: Whitechapel Gallery, 2006.

Kwon, Miwon One Place After Another: Site-specific Art and Locational Identity. Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2004.

Letters and Responses / Author(s): Liam Gillick and Claire Bishop / Source: October , Winter, 2006, Vol. 115 (Winter, 2006), pp. 95-107 / Published by: The MIT Press

Livingstone, Andrew and Kevind Petrie, eds. The Ceramics Reader. London: Bloomsbury, 2017.

Loveless, Natalie. How to Make Art at the End of the World: A Manifesto for Research-Creation. Durham: Duke UP, 2019.

McKee,Yates. Strike Art: Contemporary Art and the Post-Occupy Condition. London: Verso, 2017.

Mesch, Claudia. Art and Politics: A Small History of Art for Social Change since 1945. New York: I. B. Tauris & Co. Ltd, 2013.

Stoneman, Rod. Seeing Is Believing: The Politics of the Visual. London: Black Dog Publishing Ltd, 2013.

On Art and the Environment

Blanc, Nathalie and Barbara L. Benish. Form, Art and the Environment: Engaging in Sustainability. New York, Routledge, 2017.

Burtynsky, Edward, Jennifer Baichwal, & Nicholas De Pencer, eds. Anthropocene. Art Gallery of Ontario and Goose Lane Editions, 2018.

Davis, Heather & Etienne Turpin, eds. Art in the Anthropocene: Encounters Among Aesthetics, Politics, Environments and Epistemologies. London: Open Humanities Press, 2015.

Edwards, David. Creating Things that Matter: The Art and Science of Innovations that Last. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2018.

Giannachi, Gabriella. “Representing, Performing and Mitigating Climate Change in Contemporary Art Practice.” Leonardo (Oxford) 45, no. 2 (2012): 124-31.

Mockler, Kathryn, ed. Watch Your Head: Writers and Artists Respond to the the Climate Crisis. Toronto: Coach House Books, 2020.

O’Neill, Saffron J., and Nicholas Smith. “Climate Change and Visual Imagery.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, vol. 5, no. 1, 2014, pp. 73–87.

Quarmby, Lynne. Watermelon Snow: Science, Art, and a Lone Polar Bear. Montreal: McGill-Queens UP, 2020.

Sandilands, Catriona ed. Rising Tides: Reflections for Climate Changing Times. Halfmoon Bay: Caitlin Press, 2019.

Sommer, L. K., and C. A. Klöckner. “Does Activist Art Have the Capacity to Raise Awareness in Audiences?—A Study on Climate Change Art at the ArtCOP21 Event in Paris.” Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts. Advance online publication, July 1 2019, http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/aca0000247. Accessed 25 September 2020.

Tanahashi, Kazuaki. Painting Peace: Art in a Time of Global Crisis. Boulder: Shambhala, 2018.

Yusoff, Kathryn, and Jennifer Gabrys. “Climate Change and the Imagination.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, vol. 2, no. 4, 2011, pp. 516–534.

On the Environment

Hamilton, Clive. Requiem for a Species. Routledge, 2015.

Henson,Robert. The Thinking Person’s Guide to Climate Change. Boston: American Meteorological Society, 2014.

Latour, Bruno. Facing Gaia: Eight Lectures on the New Climate Regime. Medford: Polity Press, 2017.

Nixon, Rob. Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Cambridge: First Harvard UP, 2011.

McKenzie-Mohr, Doug and William Smith. Fostering Sustainable Behaviour: An Introduction to Community-Based Social Marketing. Gabriola Island: New Society Publishers, 1999.

Morton, Timothy. Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

Ripple, William J et al. “World Scientists’ Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice” Bioscience, December 2017, Vol. 67(12), pp.1026-1028.

Scranton, Roy. Learning to Die in the Anthropocene: Reflections on the End of a Civilization. City Light Books, 2015.

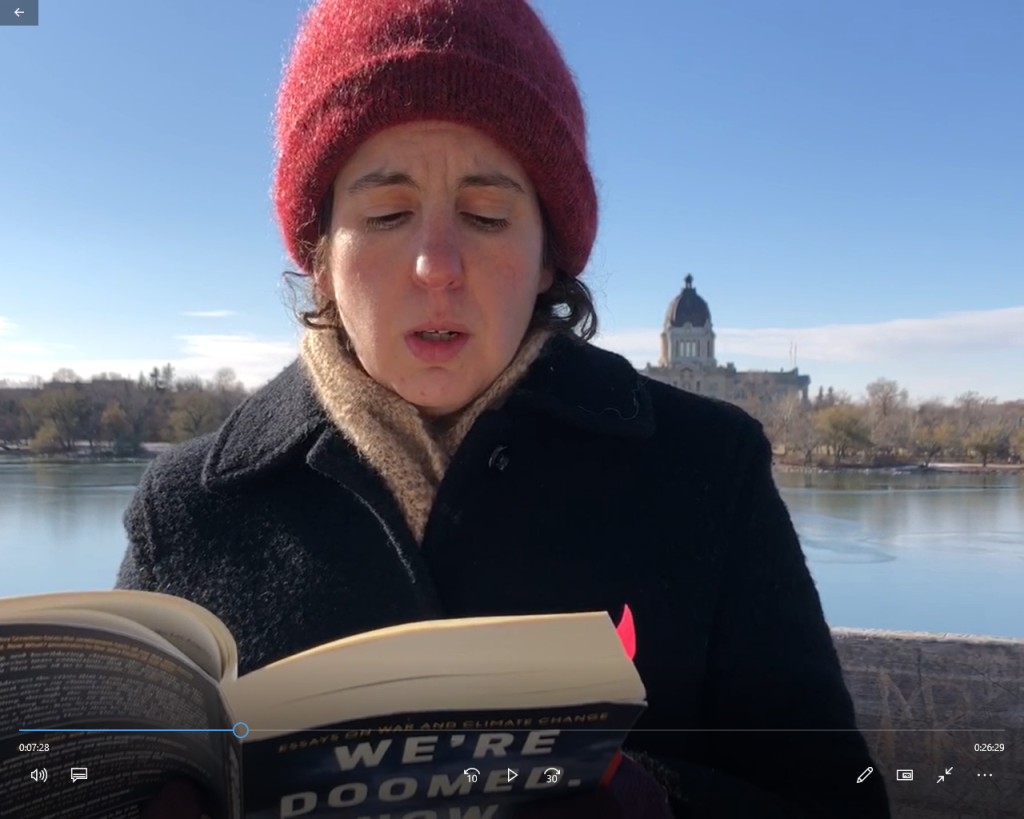

Ibid. We’re Doomed. Now What?: Essays on War and Climate Change. Soho Press Inc., 2018.

Schlossberg, Tatiana. Inconspicuous Consumption: The Environmental Impact You Don’t Know You Have. Grand Central Publishing, 2019.

Thunberg, Greta. No One Is Too Small to Make a Difference. Penguin, 2019.

Theory

Benjamin, Walter. Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings. Edited by Peter Demetz Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Inc, 1978.

Haraway, Donna J.. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, Duke UP, 2016.

Psychology (Dr. Arbuthnott’s readings lists)

Science denial:

Bjornberg, K.E., Karlsson, M., Gilek, M., & Hansson, S.O. (2017). Climate and environmental science denial: A review of literature published in 1990-2015. Journal of Cleaner Production, 167, 229-241.

Motivated reasoning:

Hennes, E.P., Ruisch, B.C., Feygina, I., Monteiro, C.A. & Jost, J.T. (2016). Motivated recall in the service of the economic system: The case of anthropogenic climate change. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 145, 755-771. Doi: 10.1037/xge0000148

Trust in science:

Hendriks, F., Kienhues, D., & Bromme, R. (2015). Measuring laypeople’s trust in experts in a digital age: The Muenster Epistemic Trustworthiness Inventory (METI). PLoS one 10(10): e0139309. Doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139309

Battiston, P., Kashyap, R., & Rotondi, V. (2020). Trust in experts during an epidemic. files.de-1.osf.io

Kraft, P.W., Lodge, Milton; Taber, C.S., 2015. Why people “don’t trust the evidence”: motivated reasoning and scientific beliefs. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 658 (1), 121e133.

Media use:

Stecula, D.A., Kuru, O., & Jamieson, K.H. (2020). How trust in experts and media use affect acceptance of common anti-vaccination claims. The Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review, 1(1). Doi: 10.37016/mr-2020-007

Huber, B., Barnidge, M., de Zuniga, H.G., & Liu, J. (2019). Fostering public trust in science: The role of social media. Public Understanding of Science, 28(7), 759-777

Strategies:

Chan, M.S., Jones, C.R., Jamieson, K.H., & Albarracin, D. (2017). Debunking: A meta-analysis of the psychological efficacy of messages countering misinformation. Psychological Science, 1-16. Doi: 10.1177/0956797617714579

Cook, J. (2017). Understanding and countering climate change denial. Journal & Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales, 150, 207-219.

Schmid, P., & Betsch, C. (2015). Effective strategies for rebutting science denialism in public discussions. Nature Human Behaviour. Doi: 10.1038/s41562-019-0632-4

Wong-Parodi, Gabrielle & Feygina, Irina (2020). Understanding and countering the motivated roots of climate change denial. Current Opinion in Environment Sustainability, 42, 60-64.

Required text: Stoknes, P. E. (2015). What we think about when we try not to think about global warming: Toward a new psychology of climate action. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing

Other readings:

Obradovick, N., Migliorini, R., Pulus, M.P., & Rahwan, I. (2018). Empirical evidence of mental health risk posed by climate change. PNAS, 115 (43), 10953-10958. Doi: 10.1073/pnas.1801528115

Medimorec, S., & Pennycook, G. (2015). The language of denial: Text analysis reveals difference in language use between climate change proponents and skeptics. Climate Change, 133, 597-605.

Griskevicius, V., Cantu, S.M., & van Vugt, M. (2012). The evolutionary bases for sustainable behavior: Implications for marketing, policy, and social entrepreneurship. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 31, 115-128.

Arbuthnott, K.D., & Dolter, B. (2013). Escalation of commitment to fossil fuels. Ecological Economics, 89, 7-13. Doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2013/02.004

Tam, K.-P., & Chan, H.-W. (2018). Generalized trust narrows the gap between environmental concern and pro-environmental behavior: Multilevel evidence. Global Environmental Change, 48, 182-194. Doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2017.12.001

Swim, J.K., Gillis, A.J., & Hamaty, K.J. (2020). Gender bending and gender conformity: the social consequences of engaging in feminine and masculine pro-environmental behaviors. Sex Roles, 82, 363-385. Doi: 10;1007/s11199-019-01061-9

Nolan, J.M., Schultz, P.W., Cialdini, R.B., Goldwtein, N.J., & Griskevicius, V. (2008). Normative social influence is underdetected. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34, 913-923.

Capraro, V., Jagfeld, G., Klein, R., Mul, M., & van de Pol, I. (2019). Increasing altruistic and cooperative behaviour with simple moral nudges. Scientific Reports, 9:11880. Doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-48094-4

Kuo, M., Barnes, M., & Jordan, C. (2019). Do experiences with nature promote learning? Converging evidence of a cause-and-effect relationship. Frontiers in Psychology, 10:305. Doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00305

Bastian, B., Brewer, M., Duffy, J., & van Lange, P.A.M. (2019). From cash to crickets: the non-monetary value of a resource can promote human cooperation. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 61, 10-19. Doi: 10.1016/j.jenvy.2018.11.002

Cunsolo, A., & Ellis, N.R. (2018). Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related los. Nature Climate Change, 8, 275-281. Doi: 101038/s41558-018-0092-2

Marlon, J.R., Bloodhart, B., Ballew, M.T., Rolfe-Redding, J., Roser-Renouf, C., Leiserowitz, A., & Maibach, E. (2019). How hope and doubt affect climate change mobilization. Frontiers in Communication, 4: 20. Doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2019.00020

Misc.

Cooper, David E.. Convergence with Nature: A Daoist Perspective. Totnes: Green Books, 2012.