This piece in my series representing Canadian glacial loss, “Athabasca Glacier: 1918-2018,” is a set of fired porcelain cups that appear to be melting. This piece embodies the unequivocal connection between our drinking water and the melting of the world’s ice.

The Athabasca Glacier is the most visited glacier in North America because it’s visible from the famous Icefields Parkway, known to be one of the most scenic drives in the world. In fact, the Athabasca Glacier is visible from the The Columbia Icefield Glacier Discovery Centre located on the parkway.

My family has made several trips to this area. While we don’t enter the Glacier Discovery Centre, or take a tour on one of the massive buses that drive onto the glacier itself, we do hike to the Wilcox Viewpoint on Wilcox Ridge that overlooks the Parkway and the glacier across from it. And we have certainly witnessed the glacier’s significant recession over the last 15 years (our first time on this hike was in 2009).

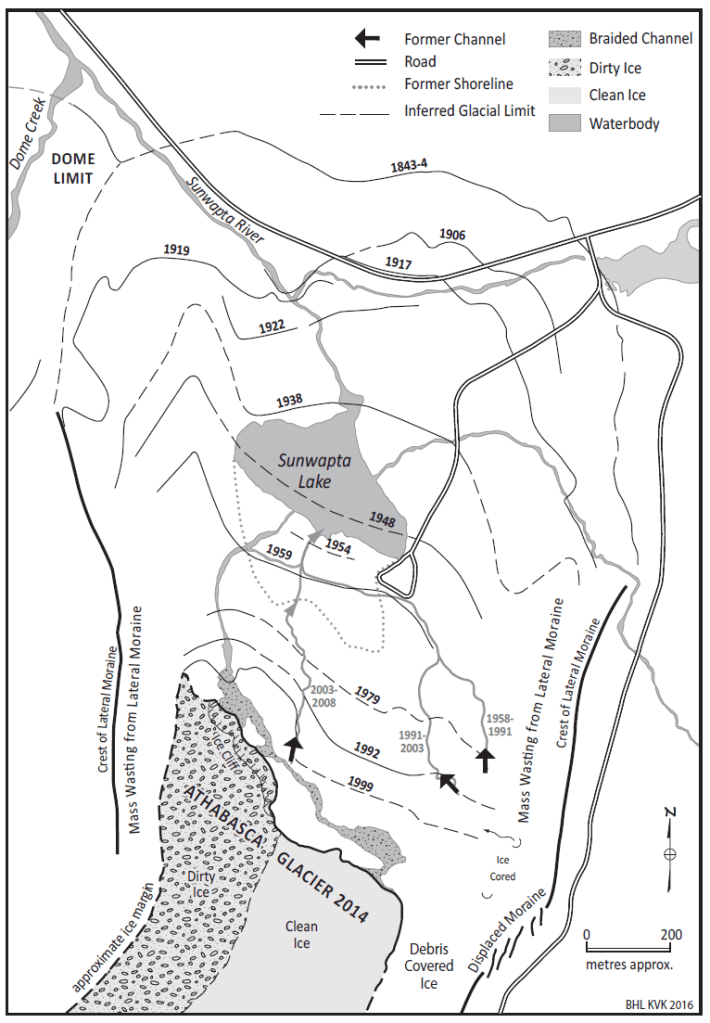

While working on this piece, I sought actual data on the recession rate of the Athabasca Glacier. Through sheer luck, I got a hold of Robert Sandford, the Senior Government Affairs Liaison for Global Climate, Emergency Response at the United Nations University Institute for Water, Environment, and Health. His book, Our Vanishing Glaciers: The Snows of Yesteryear and the Future Climate of the Mountain West has been foundational to my art practice. He put me in touch with Michael Demuth, a geoscientist, hydrologist, and glaciologist also working in the area of water security in Canada. (His book, Becoming Water — Glaciers in a Warming World, is another must-read). Michael sent me this map created by Brian Luckman, depicting the recession of the Athabasca Glacier from 1843 to 2014. I noted that in 1917, the glacier’s terminus was right on what is now the Icefields Parkway which was built between 1931-1940.

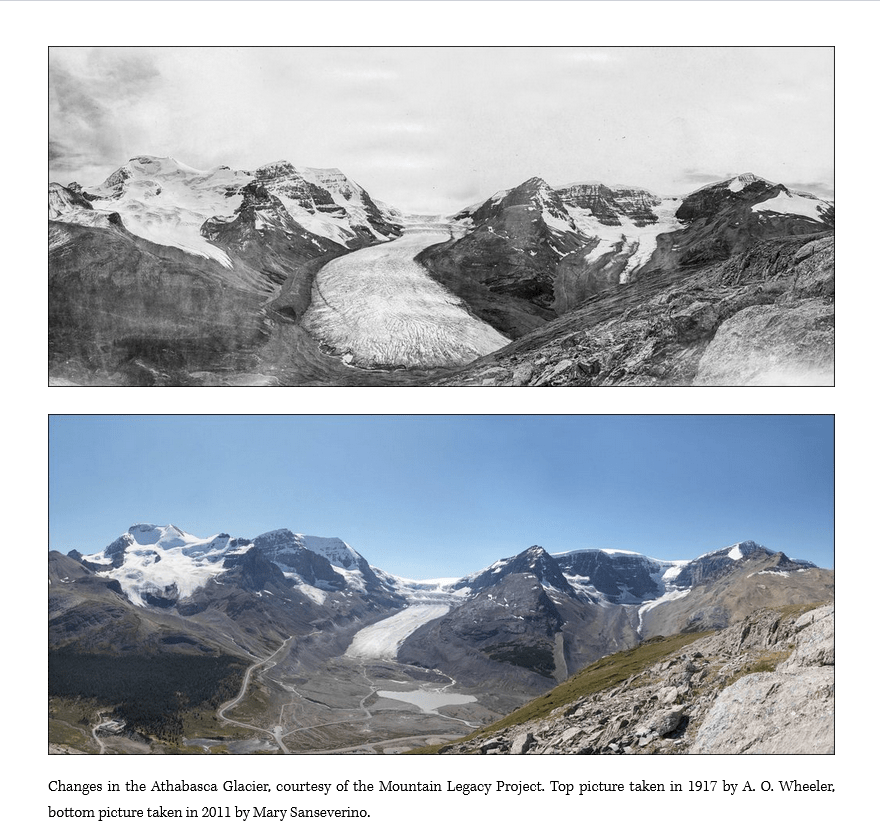

I reached out to Robert Sandford recently to tell him that he’s still an influence in my work. He replied by telling me about the upcoming United Nations International Year of Glaciers’ Preservation — 2025, which he and a colleague, John Pomeroy, dreamed up in a bar in Canmore a few years ago. Canada will join countries around the world to celebrate the greatness of glaciers and bring attention to their disappearance. The website for Canada’s contribution to this initiative has a wealth of information. Included on a page titled “The Year in Canada” are these two images of Athabasca Glacier. Notice that the vantage point for both photographs is the same:

My heart sinks when I see these images. They remind me of how I felt when I saw Athabasca Glacier for the second time, and could already detect its recession in only five years.

I hope to one day thank Bob and John in person for imagining and then helping to realize the UN International Year of Glaciers’ Preservation, and all the others working on this initiative. I’m also grateful that this project features art, including my own work, as well as science. Let’s hope that together we can make a difference.