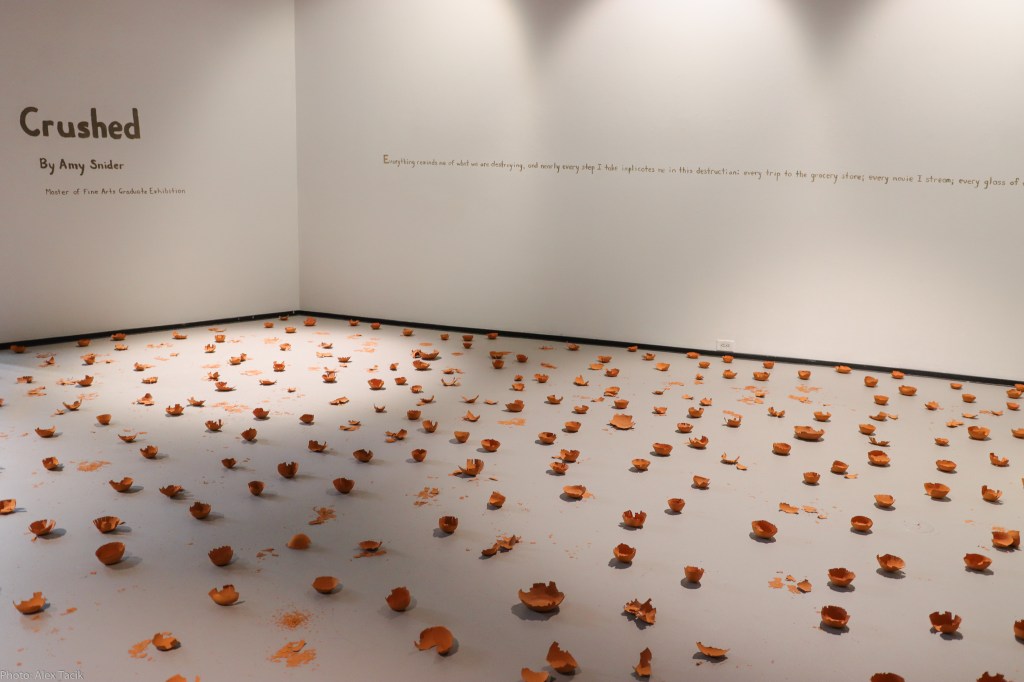

My MFA thesis exhibition, Crushed (August 2024), was a conceptual installation about climate change anxiety. The gallery floor was covered with over 2,000 eggshell thin ceramic bowls made from clay I dug up in Regina. To read a text painted onto the gallery walls with this clay, you needed to become a participant: would you step carefully between the bowls, perhaps tiptoeing or raising your pant cuffs? Or would you stomp ahead, satisfied by the sound of shattering ceramic beneath your feet? What would you leave behind for others?

The wall text circling the gallery read:

Everything reminds me of what we are destroying, and nearly every step I take implicates me in this destruction: every trip to the grocery store; every movie I stream; every glass of water I drink. Nothing I do is innocent, and the consequences are terrifying. The sky is orange, its colour the result of light bouncing off microscopic bits of wood, leaves, and pine needles that were recently forests: Jasper; Golden. Places I’ve travelled to many times, places that have healed me. In this smoke, their molecules travel to me here. Is that burnt warbler I smell? Was it scared? Did it hurt? I’m grateful to have a home to protect me from this toxic air, but what of the birds in my backyard? Birdsong used to be beautiful; now it makes me sad. I dig clay from this place, here. Touching it, I can imagine myself in another world; I can feel glaciers and lakes, forests and grasslands, flora and fauna, systems functioning the way they had for spans of time incomprehensible to us. What should I make from this clay, today, from within these broken systems? Nothing that will last. Everything reminds me of what we are destroying, and everything I create is a part of this destruction. Nevertheless, I am driven to create.

It was incredible to see how people participated with the work. During the months of preparation, I’d wondered if anyone would start off by stepping on bowls but then stop after reading the first sentence of the wall text. It was my hope that this would happen at least once. It happened several times. A few other predictions I’d made played out. Then there were the many other unanticipated interactions with the work. One young person balanced bowls across their arms and head; another squatted and spun the bowls around, making music with their unique, tinny sounds. Someone created a heart shape with the pieces of a shattered bowl. Others copied or created their own designs. A boy went racing across the floor, skipping over bowls while increasing his confidence and speed until his parents told him to stop.

I saw a few people very carefully make their way around the entire gallery without breaking a single bowl. Then, just before exiting, they purposefully held a foot over one and did it — crunch. I guess the curiosity was just too much.

Drawing people towards the gallery was a recording of birdsong that I’d made in the same garden from where I’d dug the clay. Often, people peeked in from the doorway with curiosity: what was this birdsong, and what are those objects on the floor? They hesitated, not sure if they were allowed to enter. If I caught this, I beckoned to them, telling them they were welcome. Several asked if they were supposed to break the bowls. I told them that I wasn’t there to direct them in any way—that they should interact with the work however they chose. If they asked what the show was about, I told them they could come to their own conclusions by reading the text on the walls.

Many people’s experiences of the installation were intense. From the day the show opened, I realized that I needed to be in the space whenever the doors were open. I’d try to hang out in the back office, not wanting to intrude on people as they experienced the show, but there was a steady stream of participants who would come up to me after they finished reading the text; they wanted to share how they felt in that moment. A few were crying. They each wanted to tell me about their experiences of eco-anxiety or solastalgia. I heard about childhood homelands in Mexico, Iran, and Bangladesh that are no longer the places of natural beauty they once were. Parking lots now, as the song goes.

On the second day of the exhibition, I spoke with an amazing 11-year-old who started a climate club in their school. They shared that climate change keeps them up at night. We talked for about an hour. Before they left, they told me the show helped them feel less alone and encouraged them to take more action. With that one conversation, I felt I’d accomplished more in a Masters degree than I’d ever fathomed I would. We are still in touch; I’ve become a bit of a climate-action mentor to them, and they inspire hope in me. I understood from day two of Crushed that my being present for these conversations was a part of the show itself.

Leading up to opening day, people asked me what I’d do if someone came in and crushed everything all at once. I was prepared for that possibility; I would have left all the shards in place. I was glad that this didn’t happen, but it didn’t bother me at all when I heard the occasional crunch. This was, after all, part of the experience I’d created. By the end of the week-long installation, I’d say about half of the 2,000 bowls were destroyed. I left each of them as they were, not sweeping them up nor replacing them, though I did replace the bows that I let people take with them as a souvenir.

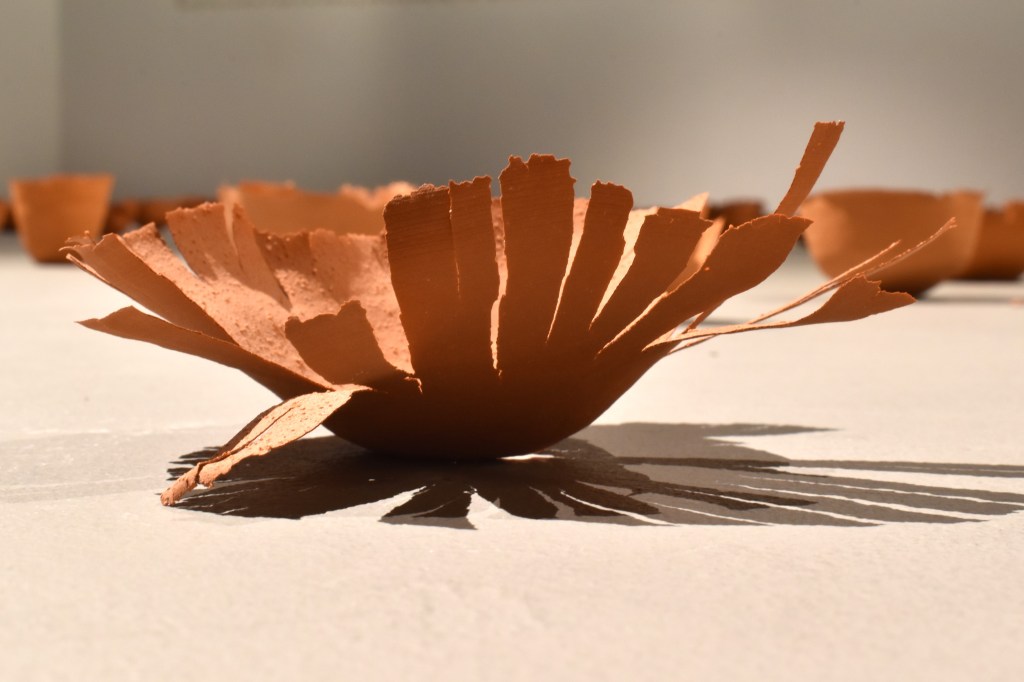

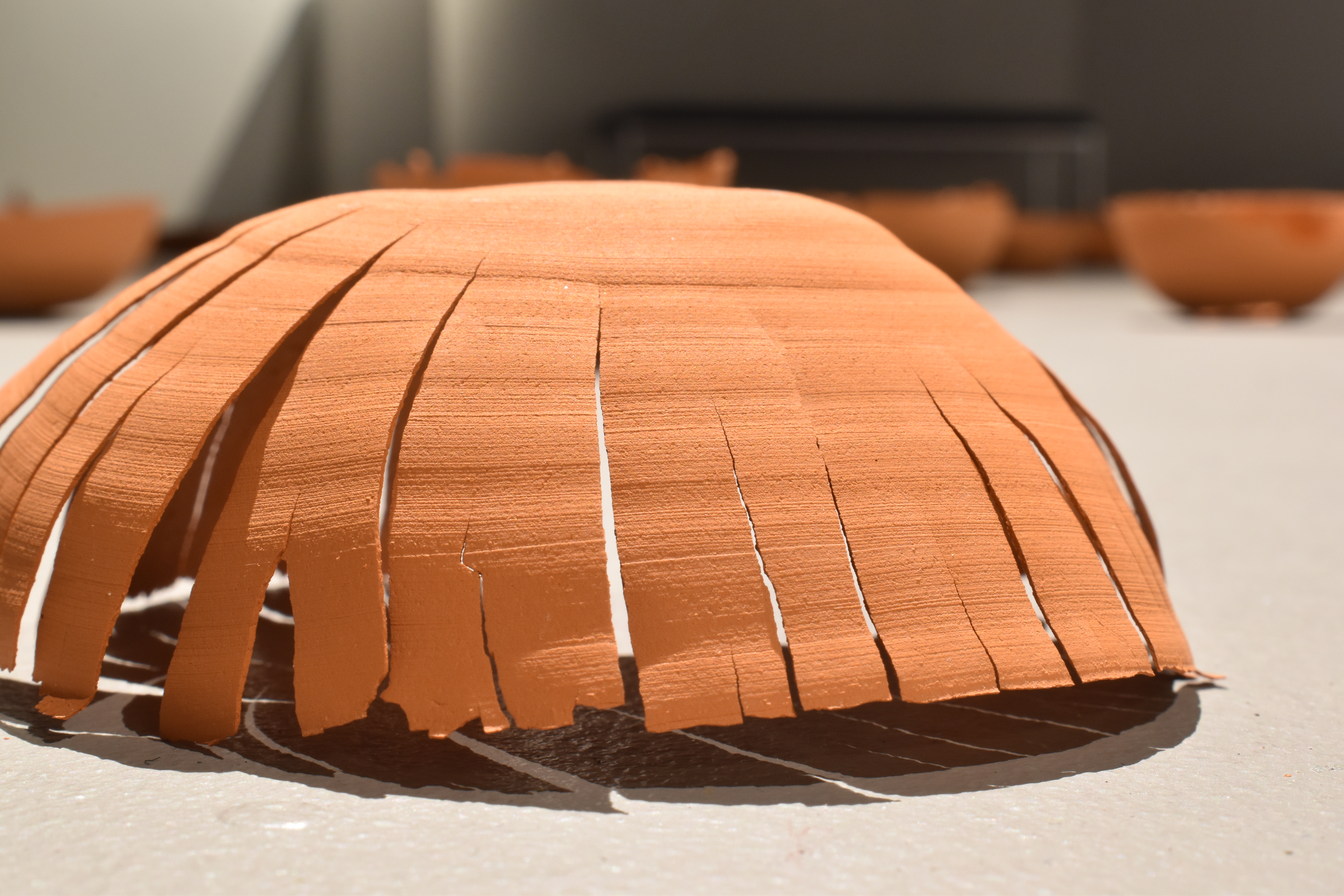

Each bowl started off already broken in its own way, many frayed and splayed into hardly-bowls-at-all. Vestiges. Unlike the pottery of long ago which we uncover today and use to learn about our past, these pots will not last. Fragile, like ourselves at this time of precarity for nearly all life on Earth, they mimic our position as a species at large, and for some, they mimic our own vulnerability. That they will not last is both their form and their content.

Through installation and hours spent sitting with the show, I got to spend time with each bowl. Without the busyness of production (plus life) that had been the previous two years, I now had time before and after the gallery’s open hours to look at each one carefully, seeing their own uniqueness up close. They became individuals again, not only elements of a whole.

I played with them, too, turning them over and noticing their different textures inside and out: the grittiness of the raw local clay captured on the inside while the outside reveals the rings my fingers left behind when I’d pulled up the walls of the bowls I’d thrown on the wheel and used as molds.

This clay remains a mystery. The way it peels and releases from just about any smooth surface is unlike all other clays I’ve encountered. I call it a magic act. At one point, I tried to break its secrets, but I soon decided to quit.

One question I’d had in the lead-up was how this installation could accommodate people with mobility issues. I realized it was a very ableist show in that the experience I’d intended was only possible for people who could walk on two feet. The whole idea was that people had to choose how they’d interact with the work on the floor. A person in a wheelchair would not have that choice. What I ended up doing when the first person in a wheelchair approached was to ask her how she wanted to engage with the installation. I offered to clear a path for her wheelchair, and she accepted. On two other occasions, I cleared this path for people to participate in the installation this way. I had an eye-opening conversation with a person in a wheelchair about the lines she drew between the lack of sufficient care in our healthcare system and our lack of care for the environment.

My ambition with Crushed was to create an environment that would bring participants’ own climate fears to the surface, show them that such feelings are justified and shared, and offer them resources and support. So often we are encouraged to be hopeful and focus on the positives. In fact, this is entirely built into the neoliberal society which is leading us towards disaster: never-mind worrying about the future, just keep calm and progress, progress, profit. We don’t often give ourselves and each other the opportunity to confront our difficult emotions about what the future may bring, emotions that are entirely reasonable given the unequivocally terrible state our natural world is in. I believe that it is important to learn how to face those feelings before they become overwhelming, as they have for me. Finding community is key to doing this. That is why at the end of the wall text was information about a non-profit support group I co-founded, EcoStress Sask, and a free discussion circle led by a psychologist and a counsellor that took place in the gallery at the end of the show.

It’s been seven months since I had the magical experience of installing and defending this work at the Fifth Parallel Gallery, University of Regina, August 20th to 27th, 2024. I would have written about it sooner, but sadly I’ve been occupied with a serious illness in my family which is actually in some ways connected to the theme of this show.

I want to thank my supervisor, David Garneau, for his dedication to my project, generosity with his time, and the knowledge and wisdom that enabled me to carry out a successful show and defense. I miss our conversations. Many thanks to my other committee members, Ruth Chambers and Holly Fay, my external examiner, Linda Swanson, and the Chair of my defense, Mel Hart. It was an honour to have the attention of these artists and scholars. A big thanks as well to the friends who helped with the installation and strike: Mona, Sana, Ashkan, and Sara. Thank you Fifth Parallel Gallery director Bree Tabin. Finally, I thank my husband, Michael Trussler, and our son, Jakob. I wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for you two.

Photo credits: Alex Tacik, Mona Navai, and myself.