This week, my assignment is to watch Hito Steyerl’s How Not to be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File, 2013 and answer the question, “What constitutes dialogue (as it pertains to an art practice; to your art practice)?”

When I consider what this video piece is doing, pointing at the fact of our constant surveillance and the panopticon of ubiquitous images, I think that it is entering into dialogue with so many other works, among them Marina Abramović’s “The Artist Is Present” (2010).

That Abramović chose to “merely” sit and look at people defies the trend in society to “disappear” people, to make them invisible, as the Steyerl satirically demonstrates. What she did by staring at 1,000 people over three months was to tell them each that they are seen. Many were brought to tears through this experience of simply (though so uncommonly) being observed.

This is in contrast to the world which Steyerl captures in this video, where, as Michel Foucault puts it in Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, with panopticism, each person

is seen, but he does not see; he is an object of information, never a subject in communication.

(Foucault 200)

This means that Steyerl entered into dialogue with Abramović by creating this work three years later. They are coming at the issue of what it means to be seen from two different angles. It’s as though Steyerl could have seen the Abramović and been inspired to respond by saying “right: this never happens; instead, images of us are everywhere and make us disappear.”

Dialogue is conversation. Works of art talk to one another each time we view them. They may talk even without us. Visual art is storytelling (usually) without words.

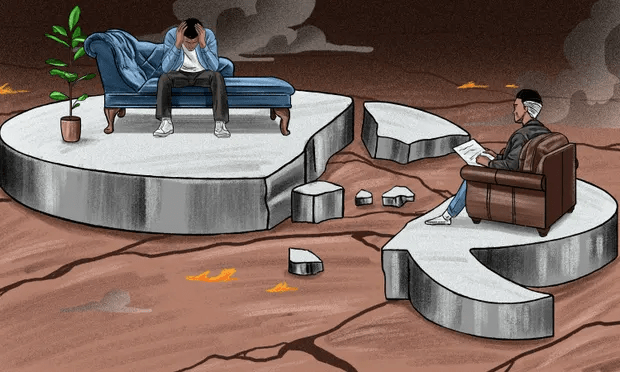

I am considering my final exhibition, and the vision I have involves covering the entire gallery floor in super-fragile cups and bowls of bright orange ceramic made from local clay. Viewers will need to enter into the space, crushing these forms as they go, to read my statement and (possibly) see videos that are projected onto the walls. Ideally, I’d also have very large rocks for people to sit on and contemplate the installation (though this may prove financially impossible). I’m curious to see who will decide to enter the show and who will turn away. I’m considering videoing the exhibit, informing people that by entering the space they are agreeing to being videoed. Were I to do this, it would be suggesting accountability: that we are being seen as we destroy the planet for future generations; that there will be a record. On the other hand, I don’t know if I want to bring that thread into the discussion. The main point is to provoke a private contemplation of the situation we’re in (with climate change) and of how it impacts us emotionally. I’d like the installation to be an acknowledgement of eco-anxiety/solastalgia. This is core. This can’t happen while we’re knowingly being surveilled. So, this videoing aspect is one of many decisions I have to make very carefully. Whatever I choose will change the conversation that this show sparks, the dialogue between between me and the viewer, and between my work and others’.

This work would also enter into a dialogue with other art dealing with climate change as well as pieces about contemporaneity. This is the moment we are in: the climate crisis is on people’s minds. As the news tells us, “Climate anxiety and PTSD are on the rise.” Art is a response to life; we will be seeing more work that addresses this anxiety that at least half of us (in North America) are experiencing.

While entering into these dialogues (with people; with other works), I hope my show will also engage in dialectics. If cups and bowls are functional items of our daily lives, why are the ones I create purposefully unusable? What is a cup if it cannot hold water? What do these cups say about their very long history of holding water? Our connection to that water? What do they say about what we take for granted in our daily lives? What we are on the cusp of losing? The ease with which they break; the jarring sound of their collapse: when did cups become so dangerous? Can we use form to talk about the destruction of form? I’d like to provoke these questions. In other words, I’d also like to enter into the dialectics of the contemporary moment itself.

According to John Molyneux in The Dialectics of Art,

Art matters because of its ability to articulate in visual imagery the social consciousness of an age, in a way that aids the development of the human personality, and our collective awareness of our natural and social environment.

This broader dialogue, these arguments about the establishment of meaning in our times, is what I strive to join with my own emerging practice.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish : The Birth of the Prison. Second Vintage Books ed. New York: Vintage Books, 1995.

One thought on “Class Post 3: dialogue and dialectics”