This past winter, as I was exploring the unique properties of Madeleine Greenway’s garden’s clay, my supervisor, David Garneau, asked me if I could think of a vessel that is more personally significant to me than a cup. After taking a moment for this to sink in (doesn’t everyone have a personal relationship with cups?), I thought of my son as that most significant vessel to me. Maybe this idea of the body as a vessel came extra quickly to me because of my training as a potter. We see vessels. As Paul Mathieu put it,

at the conceptual level, all objects are CONTAINERS. They are articulated around the transition between exterior and interior. Containment has to do with the relationship between the object and its environment. Containment bridges an object with its environment. Objects are about difference as continuity, not difference as rupture.

Mathieu 270-1

This way of seeing the world of objects is particularly clear to ceramicists, as “ceramics is the most intimate informed by this theoretical and conceptual framework, in its conflation of a volumetric form with a distinct surface” (271). I understand this notion of seeing any object, a body even, as a volumetric form. I think that my body has an understanding of forms that perhaps those who haven’t spent years handling clay, forming it, may not have. And really, what are we but lumps of clay?

I think I also jumped to my son’s body as I see him, sadly, as having some qualities in common with the cups I’ve been making lately.

Jakob is an incredibly intelligent and sensitive person who knows too much and is constantly seeking to learn more. Whereas his obsessions used to lie within the natural realm, sponging up as much as possible about dinosaurs, sharks, snakes and the like, his interest now lies in the human animal: politics. We need need watch him or he’ll sneak onto to computer to read The Guardian. A compromise is that we let him browse CBC online, but even they, in their pathetic excuse of climate crisis coverage, have headlines that spell doom and gloom, such as this one from last week, “Scientists warn future temperatures will test humans’ ability to survive.”

Knowledge about this crisis is hard to avoid in this household I guess. We make some decisions based on their climate footprint, and so of course he knows why we drive a hybrid and never use the clothes dryer. We’ve also attended climate protests together since he was just little, and I could see as he aged that he paid more attention to the placards folks were carrying, many with messages about needing to save the planet, some spelling out the situation in even more frightening terms. Sign that read “There’s no Planet B” or “How can we work when the earth is burning?” are pretty clear for anyone who stops to think about them. Not to mention the “die-in” we all once staged.

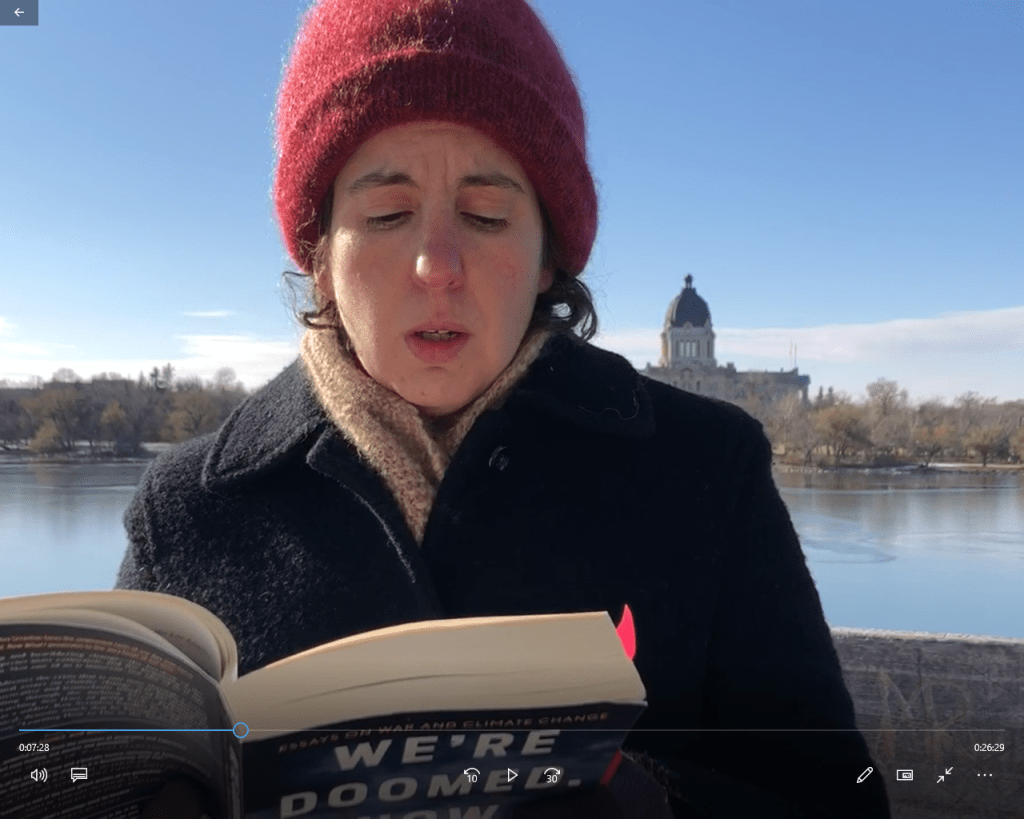

CBC reported on one protest here in Regina back in March of 2019 in the article “I’m not old enough to vote, but I’m marching against climate change.” There was a particularly good turnout in front of the legislative building for this “day of global action,” and as you can see from the photo of us in this article, I was proud to be a part of it, proud my son was a part of it.

Yes, I was proud of my son for holding up this placard. His dad and I raised him with the idea that he should be involved in this unfair fight, if not because it would get us anywhere than at least so he’d know he know to stand up and fight, and that ultimately, he did what he could for his age. I was pleased too for times when I’d get this issue in the news, thinking he’d know without a doubt that I didn’t just stand by idly while the house was on fire.

Still, I’ve realized that this awareness and participation can come at a cost for some kids, and this is increasingly on my mind these days. Jakob’s always been matter-of-fact about the reality that our species is causing problems; in fact, when he was five years old, he told me with a straight face that humans have evolved to create the next mass extinction as these things just have to happen every few million years. Lately, however, I can sense this scientific approach to the situation diminishing, or perhaps at least living alongside another perspective, one that involves worry, anger, shame, and fear.

For one thing, he’s started saying “I’m sorry” for no apparent reason up to hundreds of times a day. He’ll say it when you walk past him on the couch. He’ll say it at the breakfast table. He’ll say it when he’s brushing his teeth. When asked what he’s sorry about, he says “I don’t know, I just feel I should be sorry.” It’s a compulsion, and while we (including doctors) don’t know the cause, I have my own theory: he’s sorry for being alive.

It breaks my heart each time he utters these words.

So, this is why I’ve started hiding certain things I do from him. For instance, I did not want him to know that at the start of my MFA, when I was experimenting with performance work, I read aloud Roy Scranton’s chapter of his book We’re Doomed; Now What?, “Raising a Daughter in a Doomed World” across from the provincial legislature on the election day. I try to hide books with titles like this one from his view.

When he’s around, I also try not to talk much about my dust plates, which embody drought and as David says, a sort of “end of ceramics” tied to the end of humanity as we know it. Likewise, he was not invited to the picnic I had with Madeleine, at which we celebrated the abundance of life her garden creates while also grieving its imagined future loss.

I think that if Jakob weren’t the sort he is, clearly anxious and disturbed by what’s wrong with this world, I’d be more relaxed about it too. I’d feel less worry and guilt, at least. At the same time, I’m perfectly aware that the flip-side is also true: if I were more relaxed about all that’s wrong with this world, our son would very likely be more relaxed about it too. So really, we’re stuck being us, feeding off each others’ neuroses. Even our poor cat Toby is medicated, but still pees in our shoes over any slight shift in his daily routine. As Philip Larkin puts it so well,

They fuck you up, your mum and dad.

They may not mean to, but they do.

They fill you with the faults they had

And add some extra, just for you.

lines 1-4

I don’t want this to be true, just as I don’t want the world to be fucked up for my child. Who does? But — here’s my question — how do you raise a child in this world who knows what’s going on and can choose to participate in it, yet who isn’t entirely fucked up by it at the same time?

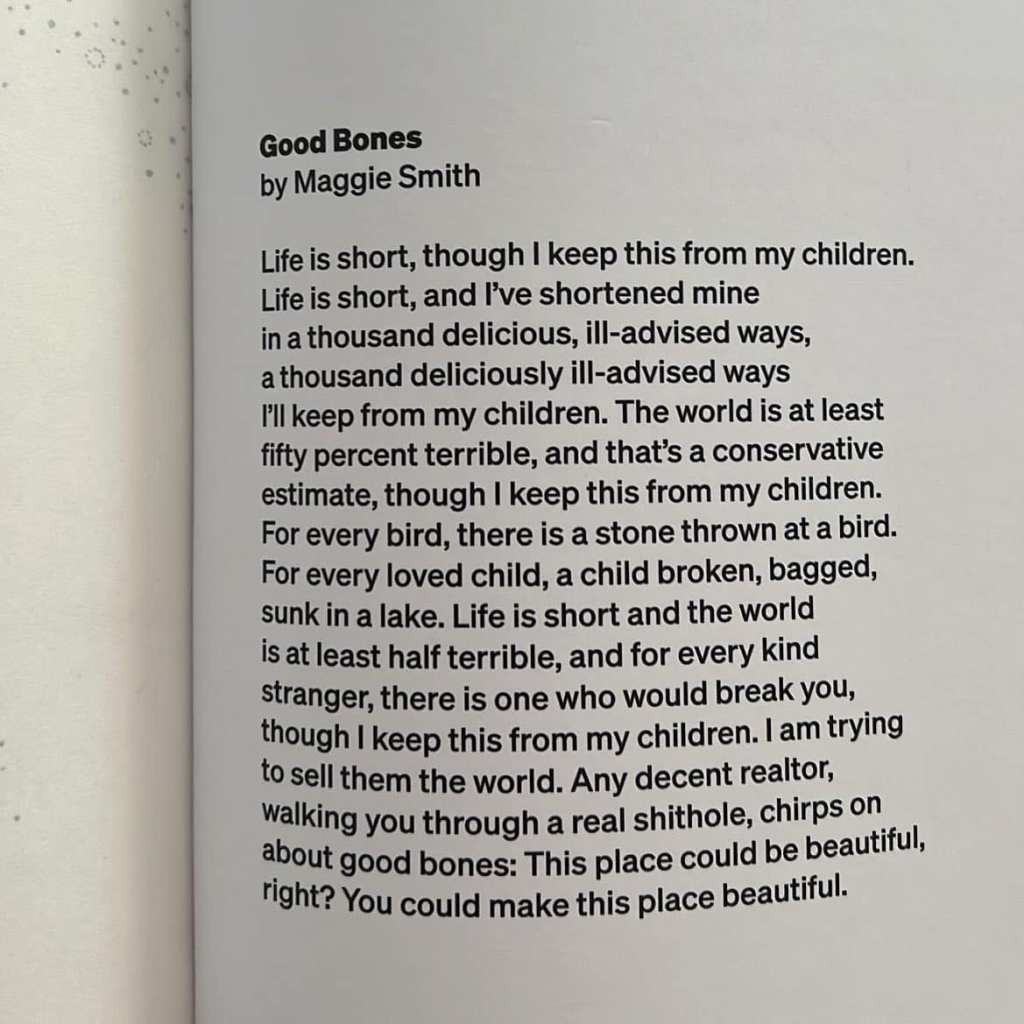

Karla McManus has generously been sharing some of her time and books with me lately, and just recently sent me this poem after a conversation we had in my studio:

I’m always trying to make this place beautiful for Jakob. It’s what every parent does. It’s what most of us try to do for ourselves as well, it’s just that some are better at it than others.

I’m realizing these days that Jakob’s place in this world is a key component of my art practice. While climate change is perhaps at the surface of my work, it’s also about larger core issues like my own anxiety and grief about the situation, which includes my anxiety and grief over my son’s anxiety and grief.

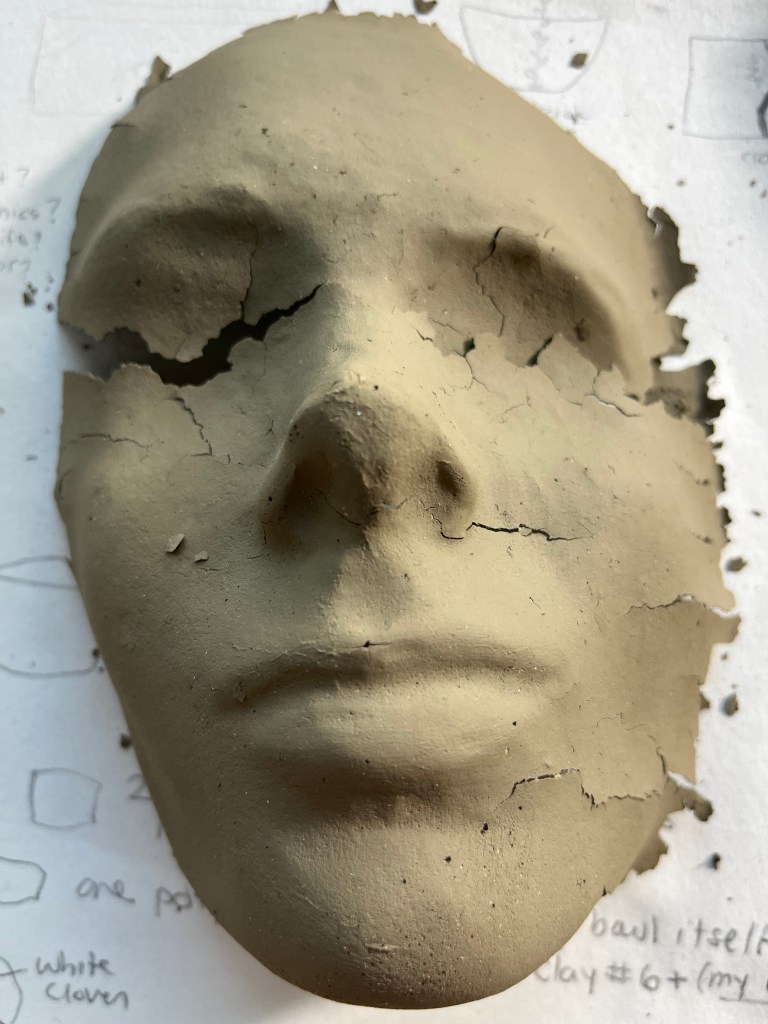

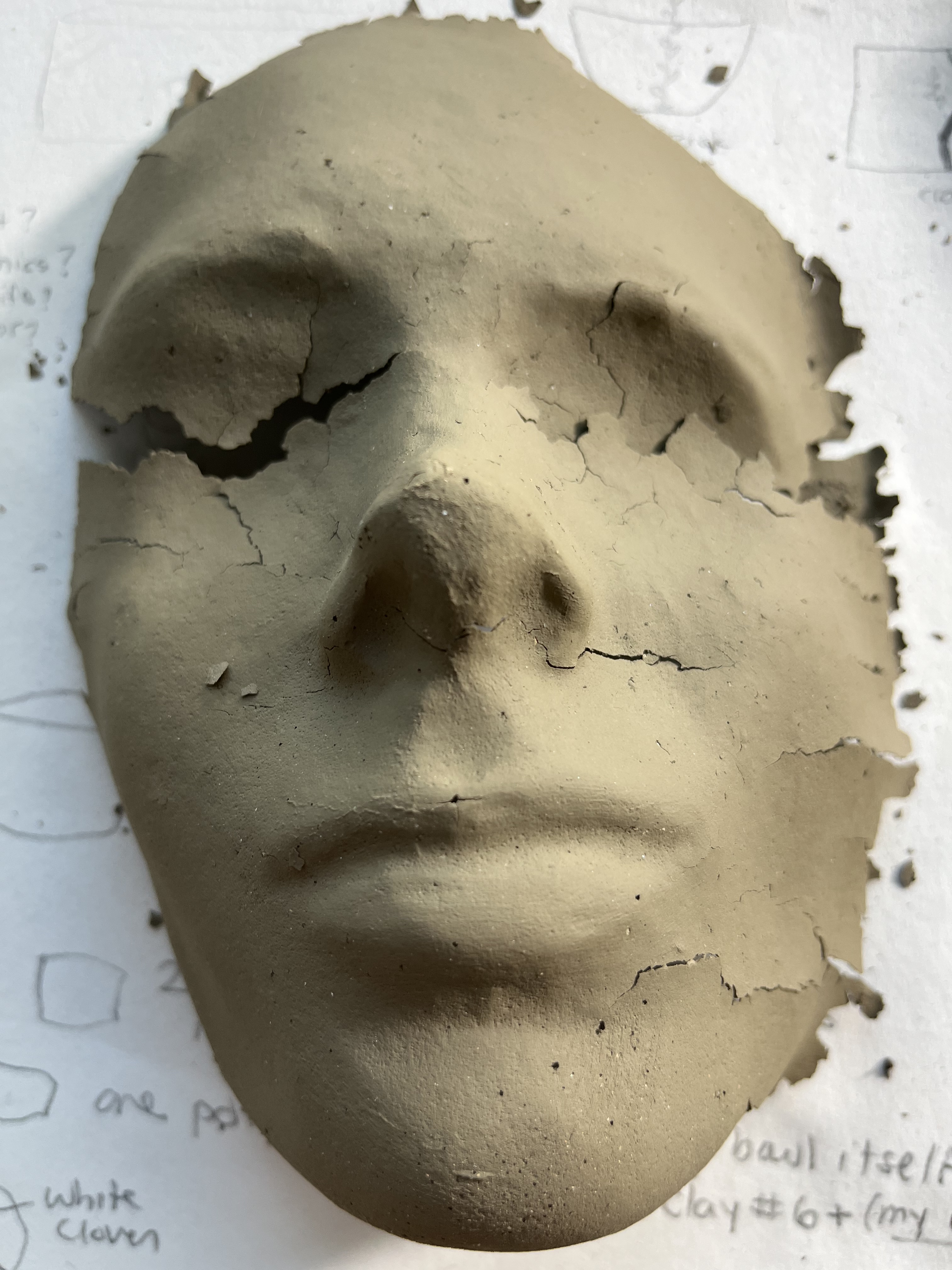

So, this must be why I immediately thought of Jakob when David asked me to consider other, more meaningful, vessels, and why this ultra thin and fragile version of his face makes complete sense to me.

The frailty of this piece aligns with the frailty I worry he has and will continue to have as climate change increasingly impinges on our lives. At the same time, I’m aware that this piece also speaks about the naturalness of this frailty. This material, this ancient clay, outlives us, and really, it is us. As I’ve written about before, the elements that comprise our bodies all come out of the ground, and back to the ground they’ll return.

I’ve explored this line of thinking by returning to an idea I had last fall while I was really, really struggling to make anything at all, and forcing myself to experiment with bringing *life* into my work with the hopes it would help shift the needle a tad from grief to hope. This idea involves planting seeds directly in the clay body and watching them germinate and grow. At the time, it worked! At least momentarily, the tiny seedlings coming from these cup forms gave me a jolt of joy, an experience of what Deborah Bird Rose refers to as “shimmer.” As I wrote in an end of semester summation that term,

Deborah Bird Rose uses the Australian Aboriginal aesthetic term bir’yuni to describe the brilliance of life as well as art: “the shimmer of life’s pulses and the great patterns within which the power of life expresses itself” (G61). She talks about how after drought, “the rains start to bring forth shiny green shoots. […] Shimmer comes with the new growth, the everything-coming-new process of shininess and health, and the new generation.”

(my post from November 2021)

Developing this more, I’ve added soil in the hollow of Jakob’s face to help the plants live longer.

I see this piece taking a turn towards other themes or ideas, ones about our connection to the land and the its cycles that I mentioned above. Paired with their uber-fragile compoent, I could frame these works as being about our struggle with oscillating on the grief—–hope spectrum, one I know many deal with from meetings of the EcoStress support group I recently created. Do I want to see my son’s face about to disintegrate into life-less clay dust, perhaps focusing on his anguish, fragility, and hopelessness, or do I wish to focus on its potential to sprout new growth from its process of decay, and what would that mean?

I feel that there’s potential here to explore one or both of these versions of Jakob’s face, but at the same time I’ve been asked by several people why I’ve chosen Jakob’s face. This is something I’ve been trying to work out.

To help me think about what faces mean, I first turned to the philosopher who’s written most on it, Emmanuel Levinas. (I owe a lot to having a husband with an enormous library). Levinas sees the face as the pinnacle expression of the Other, or what he calls Autrui. The face is the way we know someone.

In the concreteness of the world a face is abstract or naked. It is denuded of its own image. Through the nudity of face nudity in itself is first possible in the world. The nudity of a face is a bareness without any cultural ornamentation, an absolution, a detachment from its form in the midst of the production of its form.

Levinas 53

The face is the portal into our understanding of the Other. It is unique in this ability; unlike everything else, “the epiphany of the face is alive” (53). I think I was drawn to use the face because it is my entrance-way into my son’s being.

I’ve also bumped into the face in other reading I’ve done. In “On Transience,” it was serendipitous to me that Freud writes, “[t]he beauty of the human form and face vanish for ever in the course of our own lives, but their evanescence only lends them a fresh charm” (305-6). This idea of the face as something that vanishes is another possibility for what I’m on about with my paper-thin mask of Jakob; maybe my work is about our own ephemerality, regardless of climate change and eco-anxiety, just the fact that we all, including my son, are here for such a very short time.

Then, while experimenting with planting seeds in Jakob’s face, I was likewise pleasantly surprised to come across a chapter in a book Karla lent me in which Sabine Lenore Müller discusses “Environmental Modernism: Ecocentric Conceptions of the Self and the Emotions in the Works of R. M. Rilke and W. B. Yeats.” In this chapter, Müller analyzes Rilke’s poem Der Tod des Dichters, “Death of the Poet.” Here are a few of its lines:

Those who saw him alive knew not

How much he was at one with all this.

Because this: these depths, these

meadows

And these waters were his face.

Oh, his face was all this vast expanse

wanting even now still to be near him,

wooing;

And his mask, which now perishes, un-

certain, is tender, open as the inside

of a fruit, decaying in the air.

Rilke qtd in Müller 53

Wow, thank you Rilke, and thank you Müller for showing me this. The face, as an embodiment of our entire being, is really the landscape, nature itself. This is divergent from Paul Mathieu’s notion of the object. While for him, objects bridge the exterior and the interior, for Rilke, we are both of those spaces; we are everything.

As Müller points out, for Rilke,

“the face is described as a vast expanse, the environment itself, meadows and woods, to which the body, which used the human body as a mask for self-expression, yet, was obscured beneath it. In death the mask is wasting away, and the face is finally revealed — the poet’s face was the expanse of the natural world.

Müller 54

In other words, the poet in Rilke’s poem is an example of Heidegger’s Being, connected to everything else in existence. If I place this concept next to my mask of Jakob’s face, I see that through this work I am connecting Jakob to the world. Jakob becomes like Rilke’s poet he writes about, “tender, open as the inside / of a fruit, decaying in the air” (lines 16-17). Vulnerable, yet immortal. Dying, and yet alive.

I have to leave off for now. It’s been good to get all of this into writing, yet I feel like it’s still just a start. I’m not yet decided on if or how I’ll use these pieces, these faces of my son, or if I’ll find something less representational to embody him and what he/we are experiencing. It may be that I abandon the face entirely, but that it will still have informed my work, somehow.

Works Cited

Bird Rose, Deborah. 2017. “Shimmer When All You Love Is Being Trashed.” Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet, edited by Anna Tsing et al, 51-63. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Larkin, Philip. “Your Parents.” High Windows. Faber and Faber, 1974.

Levinas, Emmanuel. Basic Philosophical Writings, edited by Adriaan T. Peperzak, Simon Critchley, and Robert Bernasconi, Indiana UP, 1996.

Matthieu, Paul. “Object Theory.” The Ceramics Reader, edited by Andrew Livingstone and Kevin Petrie, Bloomsbury, 2017.

Müller, Sabine Lenore, “Environmental Modernism: Ecocentric Conceptions of the Self and the Emotions in the Works of R.M. Rilke and W.B. Yeats.” From Ego to Eco: Mapping Shifts from Anthropocentrism to Ecocentrism. Edited by Sabine Lenore Muller and Tina-Karen Pusse. Brill, 2018.

Smith, Maggie. “Good Bones.” Good Bones. Tupelo Press, 2017.

Thank you or sharing this poignant post, Amy. I trust your summer goes well. David

David Garneau Professor Head of Visual Arts University of Regina 3737 Wascana Parkway Regina, SK, S4S-0A2 1-306-450-4645

The University of Regina’s main campus is on Treaty 4 lands, which are the traditional territories of the nêhiyawak, AnihÅ¡inÄpÄk, Nakoda, Dakota, and Lakota peoples and the homeland of the Métis/Michif Nation.

LikeLike