In “The Ecology of Grief,” botanist Phyllis Windle writes about the need for society to respond emotionally to nature, and the difficulties of dealing with the grief that can come from doing so after one becomes aware of the state it’s in. While the article is slightly dated (1992), there are observations in it that are very relevant in today’s world. For instance, Windle includes Bill McKibben’s response to environmental degradation that I can associate with as we move into winter and have a break from the forest fires and heat waves:

The end of nature probably also makes us reluctant to attach ourselves to its remnants, for the same reason that we usually don’t choose friends from among the terminally ill. I love the mountain outside my back door….But I know that some part of me resists getting to know it better – for fear, weak-kneed as it sounds, of getting hurt. […] I find now that I like the woods best in winter, when it is harder to tell what might be dying. The winter woods might be perfectly healthy come spring, just as the sick friend, when she’s sleeping peacefully, might wake up without the wheeze in her lungs.

(McKibben qtd. in Windle 364)

McKibben’s words resonate with me. I find myself reluctant to attach myself to natural places, afraid of getting hurt. Even more difficult to deal with, I hurt whenever I’m in natural places that I’m already attached to, as though I’m experiencing tomorrow’s loss today. Friends have suggested to me that going for walks in nature may help me out of this serious slump I’m in. “Listen to the birds,” my swim coach told me just this morning as we were walking to the parking lot post-swim. The problem, I told him, is that these days birdsong only reminds me that birds are quickly going extinct. I feel sorry for every creature I see. I know what Windle means when she writes about the winter – less life around me means fewer reminders of what we’re about to lose. This admittedly unhealthy perception of reality, nearly an obsession, started early this summer, with the heatwaves and forest fires that took place. As I described in my first post from this semester, my trip to British Columbia this summer had the opposite effect of previous years: rather than give me comfort or solace for other stresses in my life, the natural beauty around me “only made me feel worse: all of this beauty around me is about to disappear.”

I now think that witnessing the forest fires up close on our way west was an actual experience of trauma for me. This may sound hyperbolic to some people, and some friends, only trying to help, basically tell me to get over it and enjoy what we still have. I myself have mixed feelings about my emotional response to climate change and its ensuing crises. On the one hand, I ask myself how this problem, so huge, doesn’t affect more people more seriously. How is it that we’re going on with business as usual? On the other hand, I can see how my reaction may be hard for some to understand—after all, my life is pretty good. I’m certainly experiencing nothing close to the real hardship that those least responsible for and most affected by this catastrophe are experiencing. I should appreciate my privilege, the privilege which has in fact given me the time to become aware of how bad the situation is and the time to dwell on it. I get that. People also sometimes remind me that this problem is out of my control. I know it’s good advice to accept the things I cannot change, etc., but something is making it impossible for me to heed that advice.

I suspect that much like Glenn Albrecht, the person who coined the term solastalgia, my life history at least partially explains why is that I experience “the emotional richness of contact with nature,” and therefore also “the opposite possibility, in the form of severe distress at sickness and death in nature” (24). Like others he writes about in his book, Earth Emotions: New Words for a New World,nature provided something for me during my childhood that my family did not. In short, it was always good, even when everything else around me was bad.

Albrecht defines solastalgia as

the pain or distress caused by the ongoing loss of solace and the sense of desolation connected to the present state of one’s home and territory. It is the existential and lived experience of negative environmental change, manifest as an attack on one’s sense of place. It is characteristically a chronic condition, tied to the gradual erosion of identity created by the sense of belonging to a particular loved place and a feeling of distress, or psychological desolation, about its unwanted transformation.

(38-39)

I’m concerned by his use of the word chronic and that that he isn’t the only person using it in this context. Windle also describes the risk of losing oneself to environmental grief. She explains that one reason it’s difficult to rid oneself of the distress caused by environmental degradation is that this very type of loss, unlike the loss of a loved one, is ambiguous: “Environmental losses are intermittent, chronic, cumulative, and without obvious beginnings and endings” (365). I understand her point that it feels impossible to move forward from this place of grief when the situation is still unfolding, and in fact worsening.

Another element that makes environmental grief difficult to overcome is that society doesn’t provide opportunities for it to take its normal course. Windle compares the grief that botanists like herself experience to that experienced when a loved one is dying. She talks of how “honest conversations about grief that come quite naturally at a bedside are far more difficult at a lab bench or conference table” (365). I too feel there aren’t many opportunities to speak openly about how we feel regarding the environment. Even with those in the local activist community, I haven’t had much response when I’ve mentioned what I’m experiencing. Perhaps we are all too busy fitting any activism into our already busy lives to have time for the “grief work” that Windle says is so important that we do (365). We certainly lack the mourning customs that help people recover from loss. I’ve noticed only one instance of this taking place: in a few places around the world, people have organized funerals for glaciers. In “How to Mourn a Glacier,” Lacy M. Johnson writes about her experience at the funeral for the Okjökull glacier in Iceland, an event that included installing a plaque noting its death: “It is unusual for a glaciologist to fill out a death certificate, but something concrete, like a piece of paper or a plaque, helps to make clear that the loss is irreversible” (Johnson). This ceremony allowed people the chance to concretize their loss in a way that involves ritual and community – likely two essential elements for the recovery from grief.

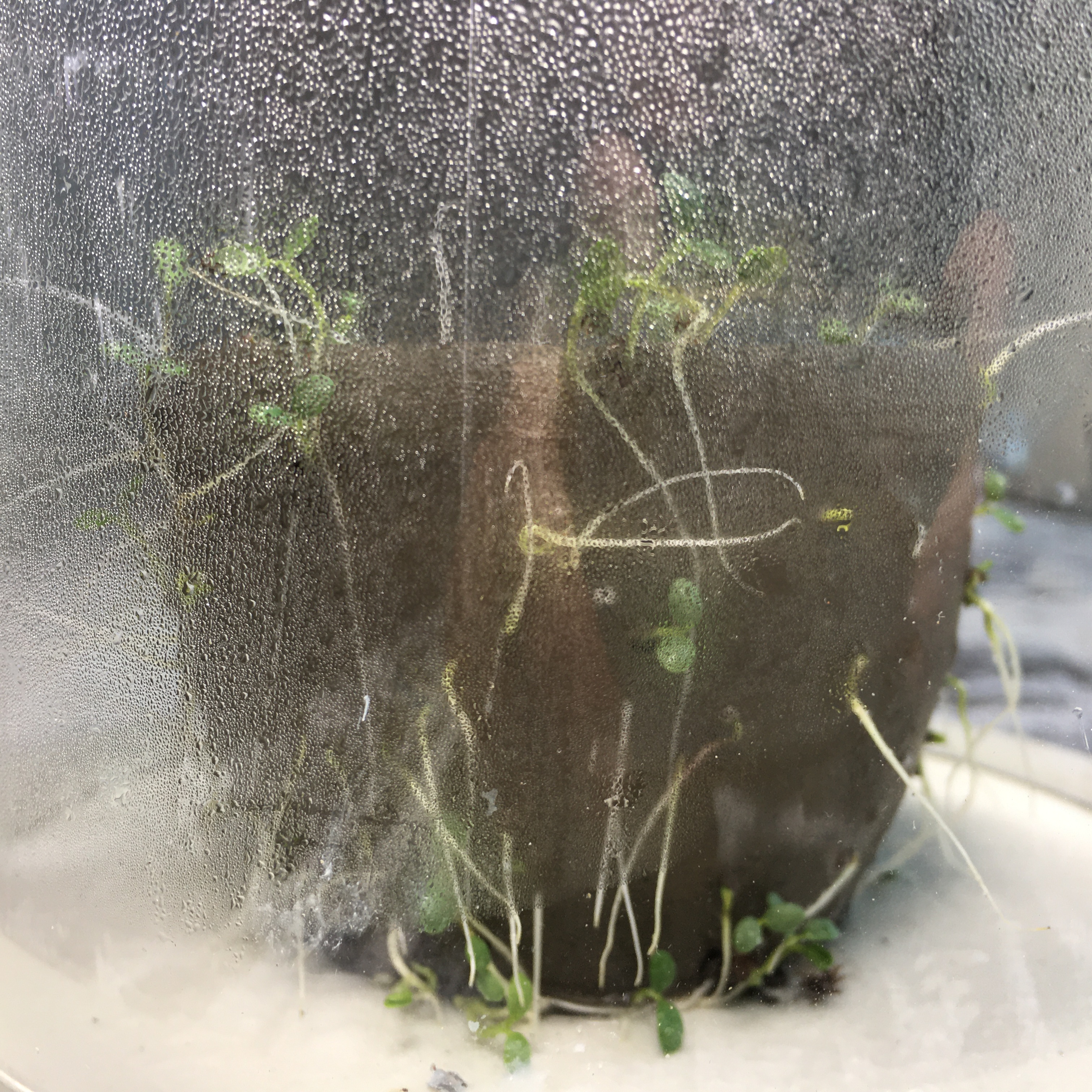

I’ve been experimenting with two ways to work through my grief in my art practice that may (I’m not sure) be incommensurate. First of all, I recently discovered that I am able to experience a small jolt of something like hope when I see life growing from my pieces made out of locally dug clay. For a few weeks I’ve been testing what happens when I add different seeds to different combinations of clay and compost, hoping to see life. It recently happened: I entered my studio to find germination taking place from a bowl I’d thrown on the wheel, and to me, it was the most beautiful thing I’d seen in a long time. I’ve repeated the steps, and the results are the same. In only one day, tiny green roots come bursting through the walls of a bowl to search for light and nourishment. I enclose these pieces under a bell jar, so they remain humid in their own small protective environments. It’s a simple act of plant reproduction, and yet it somehow feels magical to me. With a bit of water, these bowls literally come to life, and contrary to my “snowflake cups” and “dust plates,” life is what these pieces are about. However low I’m feeling, entering my studio and seeing these pieces somehow lifts my mood.

Unfortunately, the feeling subsides, and I have other periods of the day where I feel physically sick with depression and anxiety. I can’t do anything. I can hardly speak. I don’t eat. It takes all my strength to appear somewhat normal in front of my son, but I know he knows something is very wrong. I wonder, often, what I need to do to get out of this terrible place. It’s not entirely caused by solostalgia, but that is a major contributor. I think about Windle’s writing on “the benefits of grieving well” (365). She tells us, “experts urge us to grieve not only for its benefits but also because failure to grieve can have such far-reaching consequences” (365). Most crucial for me to understand is what’s in Colin Murray Parkes’ elaboration of work by Charles Darwin:

Willingness to look at the problems of grief and grieving instead of turning away from them is the key to successful grief work in the sufferer, the helper, the planner, and the research worker….We may choose to deal with our fear by turning away from its source….But each time we do this we only add to the fear, perpetuate the problems, and miss an opportunity to prepare ourselves for the changes that are inevitable in a changing world.

(Parkes qtd. in Windle 366)

I’ve been asking myself if my plant-growing bowls are a way I am turning away from the source of my grief, and if this is premature. Do I too easily allow myself to be lured in by those spindly green root tendrils? After all, these are little red clover plants that will not even be able to live out their full life cycle: they will not feel the real sun (they’re under a grow lamp); they will not reach their full size; they will not help pollinators do their work. They are entirely separated from real nature, and they will die soon. The hope they give me is entirely false. Perhaps I need to stop forcing this hope to happen and allow myself to really go through the process of grieving.

The second project I’ve just started working on is a series of small objects that would work as worry stones—ceramic pieces smaller than the palm of your hand with a smooth glossy glaze and an indentation over which it feels soothing to rub your thumb. Worry stones have a long history that I’m starting to explore. I can imagine making several of these to give away to fellow environmental activists and concerned friends. The intention would be that they’d be a sign of solidarity, an acknowledgement that we are feeling grief together. Maybe this gesture would help spark conversations and strengthen our community. Perhaps this could help us even just slightly with our “grief work.”

I’ll need to think carefully about which of these projects, or neither or both, I’ll continue with from here, assuming I’ll be able to continue making at all. I hope I will.

Works Cited

Albrecht, Glenn. Earth Emotions: New Words for a New World. Cornell UP, 2019.

Windle, Phyllis. “The Ecology of Grief.” BioScience, vol. 15, no. 5, 1992, pp. 363-366.

2 thoughts on “recent reading, thinking, and making”