There must be very few if any alive today who remember the Dust Bowl of the Dirty Thirties. It really wasn’t that long ago, even though looking at photos from that time make it seem so.

The drought of the Dirty Thirties caused the suffering of millions was a largely man-made event. Ninety years later, we are likely not going to hang dead snakes belly-up as way to put an end to drought any longer (see “Fact 9” in “25+ Mind-blowing Facts about the Dust Bowl that Happened in the 1930s“), but that doesn’t mean we’ve made much progress in learning how to stop causing it in the first place. In fact, here in Canada, we’ve undone a lot of the environmental protection support systems meant to protect us, a few which were created following the 30s. According to Marc Fawcett-Atkinson writing for Yorkton This Week in “A 1930s-era federal agency helped farms recover from an ecological crisis: It’s time for a replacement, advocates say”:

“The crisis [of the Dirty Thirties] led the federal government to create the Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Administration (PFRA), an institution that brought together agricultural researchers, engineers, and extension (community outreach) staff to help farmers use their land sustainably — a sort of Medicare for farms. “It became a body of expertise and understanding of grassland ecosystems, and grazing relationships, and biodiversity. In more recent years they were really looking into how the pasture land sequestered carbon,” said Cathy Holtslander, director of research and policy at the National Farmers Union. The PFRA endured for the next 77 years, helping Prairie farmers deal with water supply issues, develop drought and flood resilience plans, diversify their crops, and farm sustainably. Researchers with the organization also restored failed farmland into ecologically vibrant grasslands and offered free tree seedlings to farmers who supported native pollinators, slowed wind erosion, and captured carbon. “These were (among the) federal government’s positive contributions to the public good that people really valued. It was a living, concrete argument for public interest investment in people’s lives,” she said. The organization was dismantled by Stephen Harper’s Conservative government in 2013.”

Drought is going to be one of the most serious consequences of climate change that this region of Canada experiences. It’s going to get dusty.

I’ve had an interest in dust for a long time. My research paper for my MA in English (2005) was titled “‘On every new thing there lies already the shadow of annihilation’: The Fragment and Photography in W. G. Sebald’s Fiction.” Sebald is one of my favourite writers, and dust, a type of fragment, plays a major role in his books. This is most clearly displayed in the character of a painter, Ferber, in The Emigrants. Ferber’s relationship with dust is described as follows:

Since he applied the paint thickly, and then repeatedly scratched it off the canvas as his work progressed, the floor was covered with a largely hardened and encrusted deposit of droppings, mixed with coal dust, several centimeters thick at the centre and thinning out towards the outer edges, in places resembling the flow of lava. This, said Ferber, was the true product of his continuing endeavours and the most palpable proof of his failure. It had always been of the greatest importance to him, Ferber once remarked casually, […] that nothing further should be added [to the studio] but the debris generated by painting and the dust that continually fell and which, as he was coming to realize, he loved more than anything else in the world. There was nothing he found so unbearable as a well-dusted house, and he never felt more at home than in places where things remained undisturbed, muted under the grey, velvety sinter left when matter dissolved, little by little, into nothingness. (161-62)

The Emigrants. New Directions, 1997.

About this citation, I wrote that “Ferber’s ‘lava,’ ‘debris’ and ‘dust’ are clear examples of the type of physical fragment that Sebald pays special attention to in each of his books: similar to Dakyns’ office landscape of shards of written information, the remains of a charcoal drawing which is constantly erased form a collection of individual pieces of debris and dust that ultimately harden and form a different type of ‘whole’ – an encrustation of a previous fragmentation – that is also a constant reminder of an act of destruction. That this debris and dust is the ‘true product of his continuing endeavours and the most palpable proof of his failure,’ explains why Ferber’s studio interested Sebald’s narrator – he had come across another person who was so closely engrossed in the process of matter’s breakdown ‘into nothingness’ and the material remains of ruination.”

In this paper I wrote nearly 16 years ago, I was grappling with the philosophical questions of what makes a whole vs. what is a fragment, and what is artistic creation vs. destruction or failure. (All of this past study of mine was part of why I nodded when Larissa Tiggeler’s asked me if “failure” was a subject of my own work and if “it could be generative” during my End of Semester Review last term). Drought and climate change were no where on my mind back then. Now, I’ve returned to pondering dust, but more as a way of imagining what will likely be our future here on this prairie. Still, I think it’s time I refresh my memory of Sebald as well as of a few of the books in my research paper’s works cited page, including Simon Critchley’s Very Little… Almost Nothing: Death, Philosophy, Literature. I feel like there is likely something connecting this work I did in my MA and the work I’m doing now for my MFA. I also wonder what it’ll be like to reread these texts with a climate change lens.

As an aside, I came across this project by Lucienne Rickard in The Guardian three weeks ago: “‘I almost cracked’: 16-month artistic performance of mass extinction comes to a close“

Rickard used 187 pencils and 25 erasers to create and then erase 38 drawings of endangered species.

This image from the article instantly reminded me of Sebald’s description of Ferber’s studio

and of the porcelain snowflakes of “Saskatchewan Glacier” that collected on the floor of the Fifth Parallel Gallery.

I’ve started out with a stroke of luck — I happened to be in the ceramics classroom the other day when a fellow ceramics student was trimming her pots made out of my favourite porcelain, “Polar Ice.” I asked if she’d be sweeping up the refuse to slake down and reuse, sure that her answer would be affirmative. She told me that she actually doesn’t have the time to go through that process, so she throws these scraps in the garbage. (Insert wide-eyed emoji showing shock). Of course I quickly volunteered to clean up her “mess” so that I could use these fragments for this project. How serendipitous! Not only can I now rest assured that this precious porcelain material wasn’t wasted nor mined in England and transported here for me, but I also enjoyed the process of reclaiming it from the floor and surrounding furniture, gently sweeping up the smaller pieces and lifting the larger ones carefully by hand. I felt like a mushroom hunter or wildflower collector who’d stumbled upon the finding of a lifetime.

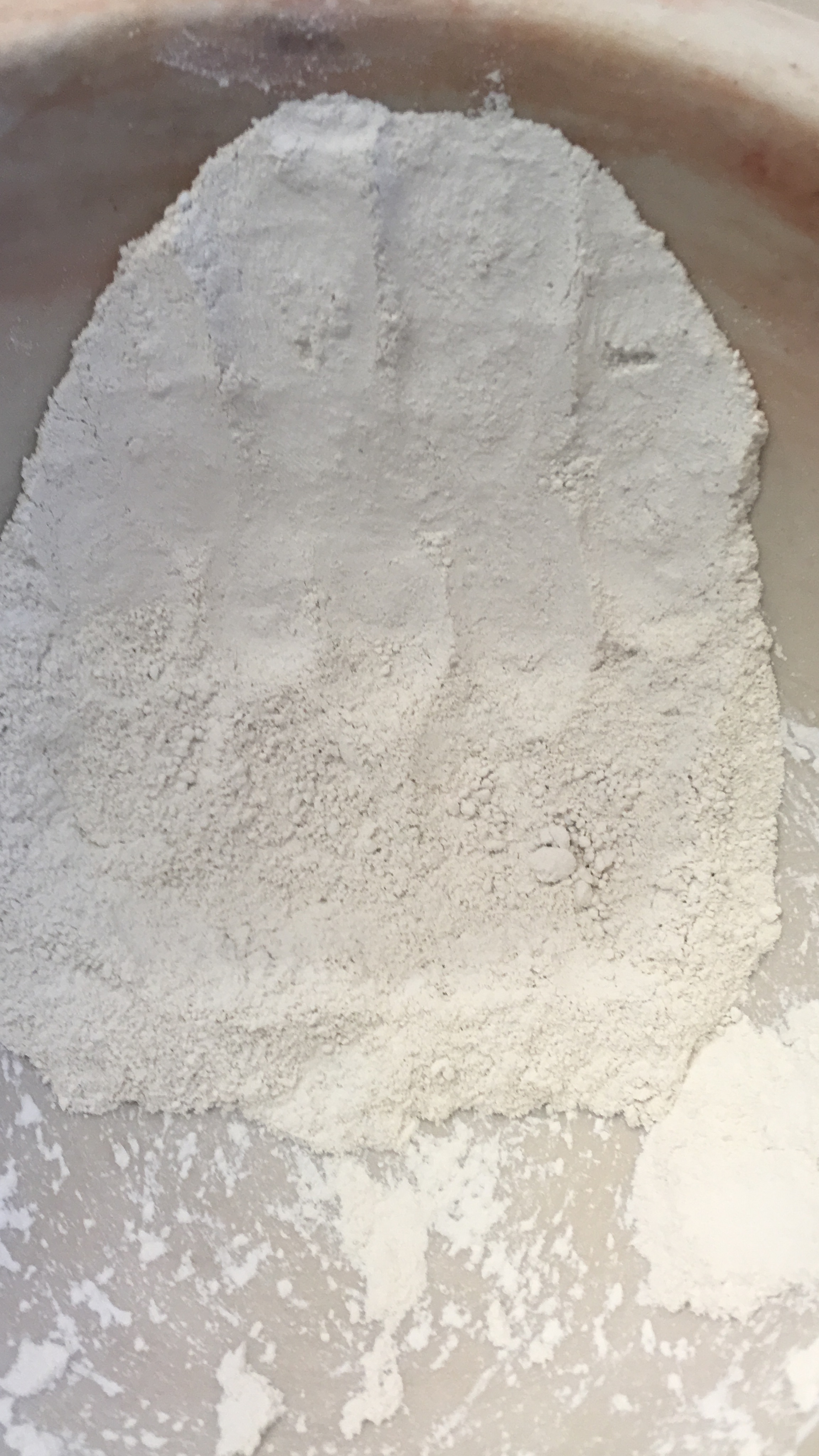

Once collected in my basket (five gallon pail), I first crushed the pieces using a heavy brick and then, in very small batches, went at them with a mortar and pestle until I had a fine porcelain “dust.”

I am so pleased that this fine dust has some structural integrity to it when pinched or pressed, as you can sort of make out in the photos below. This leaves me cautiously optimistic that my plan may succeed.

Next step is to make a press mold of this plate (which was my maternal grandmother’s)…

… and then, well, I have no idea how I’ll accomplish this, but I hope to end up with a plate made up of exclusively porcelain dust that I can then blow away.

Of course, I know this isn’t real dust — it’s not collected from drought-ridden farmers’ fields, composed of soil and atmospheric particles, nor is it contemporary household dust, comprised of pollution and dead skin cells. (Real dust these days says much about our lifestyle, often composed of microscopic plastics, traces of metals such as lead, and known carcinogens such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs)). Still, I’ll call this porcelain power “dust,” and it’ll do the trick for the metaphor I’m working with here. After all, plates are often made of porcelain, and plates are used to hold food. Food is hard to grow during a drought.

prairies — agriculture — food —> plates <— dust — hunger — drought

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():saturation(0.2):brightness(10):contrast(5):format(webp)/GettyImages-3430458-57222fb15f9b58857d9c4496.jpg)

3 thoughts on “dust”